Monday marks the 60th anniversary of the disappearance of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who helped to save tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Nazis.

More than a decade after he vanished from Budapest, the USSR acknowledged that he had been seized by Soviet troops. The authorities said he had died in a Russian prison, but the circumstances of his death are still shrouded in mystery.

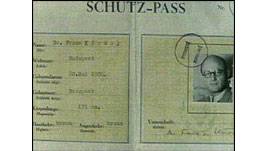

Wallenberg saved Jews by giving them Swedish passports

Wallenberg saved Jews by giving them Swedish passportsIn 1998, I spent four days working as a translator for a research group trying to find evidence supporting reports that Wallenberg may have still been alive long after 1947 when, according to the official Russian version, he died of a stroke.

Our minivan struggled its way from Moscow to the town of Vladimir through a blinding blizzard, unusual for early April.

In addition to its architectural treasures, this ancient Russian town is home to one of the country’s most notorious prisons – Vladimirsky Central. In Stalin’s times it served as a collector for prisoners before they were transferred to concentration camps in Siberia and the Far East.

Glimmer of hope

After World War II, it accommodated many high-profile prisoners, including German generals, members of East European governments, and Baltic and Ukrainian anti-Soviet guerrilla leaders.

Evidence provided by several former prisoners gave researchers hope that Wallenberg could have been held there in the early 1950s.

If proved, it could substantiate claims that Wallenberg was seen in the USSR as late as in the 1970s.

Wallenberg was 33 when he disappeared – so he would have been 86 if he was still alive

The theory that he had survived didn’t sound too incredible, considering the fate of the Hungarian World War II prisoner Andras Tamas who was found in a Russian mental hospital in the 1990s and returned to Hungary after 55 years.

Wallenberg was 33 when he disappeared – so he would have been 86 if he was still alive when we went to Vladimirsky Central.

Former prisoner

The group was headed by Marvin Makinen, who found himself in this very prison after being arrested in Kiev, where he came on tourist trip as a left-leaning student in the early 1960s.

The group also included software expert Ari Kaplan from New York and two historians from the Russian human rights organization Memorial.

High-profile prisoners were identified with numbers rather than names

The task was to scan thousands of prisoners’ ID cards covering the period when Wallenberg could have been in the prison.

Most precious for the research were the cards of people identified by numbers rather than real names. These were supposed to be high-profile cases, such as Wallenberg’s.

Mr Kaplan was to analyse the records in order to establish who could have been in contact with the ”numbered” prisoners and therefore could shed light on their true identity.

Total terror

The checking of cards revealed the epic proportions of repressions, whose victims included not only all ethnic groups and social strata of the USSR, but thousands of foreign nationals who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and were consumed by the Soviet prison system.

There were thousands of cards of female prisoners from the areas near Moscow that were under German occupation during the war.

Those were accused of ”illicit relations with the occupiers”, but I was told that nearly all young women on territories reclaimed by the Red Army were suspected of this and taken prison.

There was some amusement, too. I found a card of an Odessa-born Jewish man who spent more than half a century in prison for a succession of political crimes he committed after being put behind bars.

”This is a resistance hero,” I exclaimed, but the Memorial researchers only laughed.

They said he was a tattoo artist who made political tattoos on the bodies of ordinary criminals who believed that they could improve their conditions by being reclassified as political prisoners.

”Slave of the USSR” on one’s forehead was among the most popular.

The prison personnel were quite cooperative, especially a young officer considered the local computer whiz kid, who seized the opportunity to learn more about modern software.

But we did not get to see many prisoners, except cooks in the local canteen, where we were allowed to eat.

Like many other attempts to find traces of Raoul Wallenberg, this one failed to lead to a breakthrough, but I hope that the information that was gathered helped Memorial’s effort to draw a complete picture of the scope and structure of Soviet state terror.