By MAX GRUNBERG, DAVID MATAS, SUSANNE BERGER

What happened to the Swedish diplomat that saved thousands of Jews from Nazi persecution?

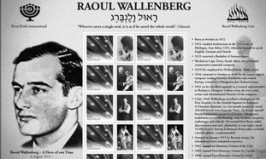

With Russia’s failure to produce conclusive evidence about the fate of Raoul Wallenberg in Soviet captivity, the Swedish government must continue to press for direct access to essential archives and to locate witnesses who may have factual information about what happened to the Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Hungarian Jews from Nazi persecution in 1944, only to disappear himself in the Soviet Union in 1945.

For decades, Russia has claimed that Raoul Wallenberg died on July 17, 1947, in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. Yet in 2009, Russian officials finally admitted that Wallenberg had been interrogated as late as July 23, 1947, six days after his official death date. It also became clear that Russia had intentionally withheld this crucial fact from an official Swedish-Russian working group that had investigated Wallenberg’s fate from 1991-2001.

In spite of numerous requests to Russian authorities to produce uncensored copies of the July 23, 1947, Lubyanka interrogation register and related documents, Russian officials so far have not released any additional records to show what happened to Raoul Wallenberg after this date. The new information proves that vital documentation about the case continues to exist in Russian archives and that the case can and should be solved.

Russian officials have repeatedly stated that they “continue to assist Sweden in replying to specific requests for additional information about the fate of Raoul Wallenberg.” However, Russian officials have not allowed scholars access to a variety of key files and materials that remain classified in Russian archives and that are essential for solving the case.

In addition to the previously cited prison interrogation registers, this material includes – among other things – Soviet foreign intelligence records from Hungary and Sweden for the period 1943-1945, which would shed light on the reasons why that Soviet authorities decided to arrest Wallenberg; and uncensored access to investigative files of a number of prisoners closely associated with Raoul Wallenberg in captivity, as well as key correspondence records between the Soviet security services and the Soviet leadership – such as the Central Committee and the Politburo – which would reveal how Soviet leaders handled Wallenberg’s[his what?] before and after 1947.

Until this documentation has been reviewed, no final conclusions about Wallenberg’s fate can be drawn. What is the Swedish government doing to ensure that Russian authorities provide access to this documentation? The answer is, unfortunately, “not much.”

As stated on the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s website, the full clarification of this issue remains an important priority: “The main purpose of research studies should be to produce conclusive evidence regarding Raoul Wallenberg’s ultimate fate and, if he is still alive, enable him to return to Sweden.”

However, the Swedish Foreign Ministry considers the Wallenberg case a historical issue and has therefore chosen not to make any direct requests for clarification about “Prisoner Nr. 7” to Russia’s President Dmitry Medvedev or his elected successor, the current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. Instead, official Swedish demands have been limited to asking Russia merely for an “open archival policy.”

ON JANUARY 17, 2012 of this year, the Associated Press widely reported that in 1991, Russia’s Security Services had actively interfered with the work of the first official International Wallenberg Commission when it was trying to review relevant records in Russian archives. Swedish Foreign Minister Card Bildt immediately announced that he would be sending Ambassador Hans Magnusson on a fact-finding mission to Moscow to determine what additional information about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate remains available in Russia.

As former Swedish chairman of the Swedish-Russian working group, Magnusson is well qualified for the task. However, while the dispatching of a special emissary to Russia to request an “update” about the Wallenberg case is undoubtedly welcome, implementing procedures to ensure meaningful access to important documentation so that a credible investigation can be conducted is quite another. It remains to be seen how the Swedish Foreign Office structures this new official inquiry so that it does not turn out to be simply a play for the galleries.

Unfortunately both Mr. Bildt and Mr. Magnusson have already publicly stated that “we should not have great expectations” of about the new efforts, essentially consigning the inquiry to failure before it has even gotten off the ground. This attitude is unfortunate, especially since Mr. Bildt apparently felt that additional official steps in the Raoul Wallenberg case had become warranted.

A scheduled conference on Wallenberg in Moscow on May 28, 2012, coordinated by the Institute for Contemporary History of the Russian Academy of Science and co-sponsored by the Swedish Foreign Ministry, does not plan to address the question of his fate, and the issue will receive only a fleeting mention in the week-long program surrounding the conference.

Over more than six decades, Sweden has made surprisingly little efforts to engage international organizations and institutions in the search for Raoul Wallenberg. It took a full six years after his disappearance, until 1951, before Swedish officials asked US authorities for assistance in the case. In 1995, the International Red Cross headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, confirmed that “the subject of… Raoul Wallenberg is known to us only from the press and different campaigns organized on his behalf.” Although the head of the Swedish Red Cross, Folke Bernadotte, had sent an appeal to help locate Raoul Wallenberg to his Soviet counterpart by January 1947 to help locate Wallenberg, no official case record seems to have ever been established with the ICRC.

Similarly surprising is the fact that Sweden has so far not filed a formal motion concerning Raoul Wallenberg with the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearance. The UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, was adopted on December 20, 2006, by the UN General Assembly and addthe convention /came into force on December 23, 2010. The convention specifically safeguards the rights of the victims and their relatives “to know the truth regarding the circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person.”

With the help of other countries, Sweden could pursue additional ways to press Russia for the truth about Raoul Wallenberg. On April 19, the US Congress honored Wallenberg, who is an honorary American citizen of the US, with the Congressional Gold Medal.

As it happens, the US Senate is currently debating the repeal of the so-called Jackson-Vanick Amendment. Adopted in 1974, that amendment has long been a thorn in Russia’s side since it makes trade with Russia contingent on allowing Jewish immigration. Several US lawmakers and Russian human rights advocates have called for a linkage between Russia’s compliance with international human rights laws and the lifting of the Jackson-Vanick Amendment. They are sponsoring a bill called the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2011.

Magnitsky, a lawyer, died in Russian custody two years ago after publicizing numerous corrupt practices. The Magnitsky Act provides for a number of prominent Russians to be included on a US visa ban list and to have their assets frozen in the US. Sweden could and should demand that the full truth about Raoul Wallenberg is also be added as a requirement before repeal of the Jackson-Vanick Amendment can proceed.

In recent months the Swedish Foreign Ministry has rejected a number of other measures aimed at obtaining clarity about Mr. Wallenberg’s fate, including a request (filed by Raoul Wallenberg’shis sister-in-law, Matilda von Dardel, and other relatives) that Interpol issue a so-called “Yellow Notice” in the case, an international alert that would allow police agencies in member countries to become actively involved in the efforts to determine his fate by assisting in the location of witnesses and by taking other investigative measures.

The Russian Federation is a member of Interpol, and in 2008 Vladimir Putin personally addressed its General Assembly meeting in St. Petersburg. Already in 2007, Interpol’s Secretary-General Ronald K. Noble had confirmed in a letter that his agency would in principle be willing to issue a Yellow Notice on behalf of Raoul Wallenberg if the Swedish National Central Bureau would officially file such a request.

After delaying a decision for years, the Swedish government formally rejected the request for a Yellow Notice this past January 2012, stating that it would complicate Sweden’s political working relationship with Russia, including in the area of archival research. While this is undoubtedly an important concern, unless Sweden can move Russia to provide meaningful access to its records in the Wallenberg case, the Swedish government will have to find additional ways to ensure that researchers can conduct a proper inquiry. The matter should be treated with great urgency. The Swedish government should be sure to use every resource at its disposal to encourage witnesses to step forward before it is too late.

Moreover, Swedish officials should work more closely with countries like the United States, Canada and Israel, the International Red Cross, international police agencies, including such as Interpol, various human rights groups and national intelligence services, as well as qualified experts and scholars to press Russia to finally reveal all available facts in the case.

Max Grunberg is founder of the Raoul Wallenberg Honorary Citizen Committee, Israel. David Matas is an international human rights lawyer. Susanne Berger is a historical researcher and Wallenberg expert.