The Journal of Leadership Studies, 1997, Vol. 4, No. 3

Profile of a Leader:

The Wallenberg Effect

John C. Kunich

Air Force Space Command

Richard I. Lester

Air University

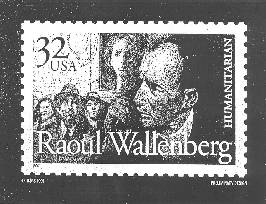

Recently, the United States Postal Service released a stamp to honor the memory of Raoul Wallenberg. The Journal felt it should re-share the original case study published here in honor of this occasion.

Executive Summary

This is a study of the leadership principles employed by Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat who went to Budapest in 1944 to intervene on behalf of Hungary’s 700,000 Jews who were being deported by the Nazis to extermination camps. This extended case narrative profiles the extraordinary accomplishments of a truly unique leader. The leadership implications addressed herein are timely, because the study of leadership is beginning to overcome decades of intellectual neglect.

Wallenberg is credited with having saved close to 100,000 lives. On 5 October 1981, the President and Congress recognized Wallenberg’s contribution to humanity when they named him only the second person ever to be awarded honorary United States citizenship; the other is Winston Churchill. By joint resolution, the United States Congress also designated 5 October 1989 as Raoul Wallenberg Day. In addition, the street in front of the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., has been renamed Raoul Wallenberg Plaza.

Leadership is movement in a resistant medium. Leadership is also the capacity to translate intentions into reality and sustain them. Leaders take charge and make things happen. They create a new reality for the purpose they serve. This case study is intended to demonstrate how Wallenberg exercised leadership and how he refused to be indifferent, complacent, or ignorant of the suffering of others. Wallenberg emerges from a sordid chapter in human history as a courageous and compassionate leader–a symbol of the best mankind has to offer.

During the waning months of World War II, the Allies were desperate for ways to stop Hitler’s slaughter of innocent civilians in Eastern Europe. Even as the prospects for an Axis military victory dimmed, the Nazis grew more determined to complete the ”final solution.” Death camps operated at maximum capacity in a feverish effort to rid Europe of Jews and other target groups. Until a complete military triumph could be secured, the Allies were powerless to halt the genocide raging on behind enemy lines. Therefore, a volunteer was sought–someone who could go where Allied tanks and aircraft could not, and disrupt the insidious Nazi death machine.

No one could have been a less obvious choice for this mission than Raoul Wallenberg. Wallenberg was 32 years old in 1944, a wealthy upper-class Swede from a prominent, well-respected family. Sweden’s neutrality in the war was only one in a long series of ready-made excuses life had handed young Wallenberg, had he wanted to use them to refuse the rescue mission. He was not Jewish; he was rich; he was well-connected politically; he was in line to take the helm of the vast Wallenberg financial empire; he had everything to lose and nothing to gain by accepting this challenge.

Wallenberg was recommended for this endeavor by Koloman Lauer, a business partner who was involved with the new War Refugee Board. Lauer felt that Raoul possessed the proper combination of dedication, skill, and courage, despite his youth and inexperience, and that his family name would afford him some protection. Wallenberg proved eager to serve, but he boldly demanded and was granted a great deal of latitude in the methods he would use.

When he learned that Adolf Eichmann was transporting roughly 10,000-12,000 Hungarian Jews to the gas chambers each day, Wallenberg hastily prepared to travel to Budapest. His ”cover” was that of a diplomat, with the official title of first secretary of the Swedish legation. He conceived a plan whereby false Swedish passports (Schutzpasse) would be created and used to give potential victims safe passage out of Nazi-controlled territory. In conjunction with this, a series of safe-`houses would be established within Hungary, in the guise of official Swedish legation buildings under diplomatic protection. With this scheme still forming in his mind, ”Swedish diplomat” Wallenberg entered Hungary at the request of the United States War Refugee Board and his own government on 6 July 1944, with a mission of saving as many Hungary’s Jews as possible from Nazi liquidation.

He designed the fake passports himself. They were masterpieces of the type of formal, official-appearing pomp which was so impressive to the Nazis. Wallenberg, though young, had traveled and studied extensively abroad, both in the United States (where he attended the University of Michigan as a student of architecture) and in Europe, and he knew how to deal with people and get things done. He worked hard at understanding enemies as well as allies, to know what motivated them, what they admired, what they feared, what they respected. He correctly concluded that the Nazis and Hungarian fascists (Arrow Cross) with whom he would be dealing responded best to absolute authority and official status. He used this principle in fashioning his passports as well as in his personal encounters with the enemy.

Wallenberg began with forty important contacts in Budapest, and quickly cultivated others who were willing to help. It is estimated that under Wallenberg’s leadership he and his associates distributed Swedish passports to 20,000 of Budapest’s Jews and protected 13,000 more in safe houses that he rented and which flew the Swedish flag. However, Eichmann continued to pursue his own mission with fanatical zealous devotion, and the death camps roared around the clock. Trains packed with people, crammed eighty to a cattle car, with nothing but a little water and a bucket for waste, constantly made the four-day journey from Budapest to Auschwitz and back again. The Hungarian countryside was already devoid of Jews, and the situation in the last remaining urban enclaves was critical. And so Wallenberg himself plunged into the midst of the struggle.

Sandor Ardai was sent by the Jewish underground to drive for Wallenberg; Ardai later told of one occasion when Wallenberg intercepted a trainload of Jews about to leave for Auschwitz. Wallenberg swept past the SS officer who ordered him to depart. In Ardai’s words,

”Then he climbed up on the roof of the train and began handing in protective passes through the doors which were not yet sealed. He ignored orders from the Germans for him to get down, then the Arrow Cross men began shooting and shouting at him to go away. He ignored them and calmly continued handing out passports to the hands that were reaching out for them. I believe the Arrow Cross men deliberately aimed over his head, as not one shot hit him, which would have been impossible otherwise. I think this is what they did because they were so impressed by his courage. After Wallenberg had handed over the last of the passports he ordered all those who had one to leave the train and walk to the caravan of cars parked nearby, all marked in Swedish colours. I don’t remember exactly how many, but he saved dozens off that train, and the Germans and Arrow Cross were so dumbfounded they let him get away with it!” (Bierman 91)

As the war situation deteriorated for the Germans, Eichmann diverted trains from the death camp routes for more direct use in supplying troops. But all this meant for his victims was that they now had to walk to their destruction. In November 1944 Eichmann ordered the 125-mile death marches, and the raw elements soon combined with deprivation of food and sleep to turn the roadside from Budapest to the camps into one massive graveyard. Wallenberg made frequent visits to the stopping areas to do what he could. In one instance, Wallenberg announced his arrival with all the authority he could muster, and then,

”You there!” The Swede pointed to an astonished man, waiting for his turn to be handed over to the executioner. ”Give me your Swedish passport and get in that line,” he barked. ”And you, get behind him. I know I issued you a passport.” Wallenberg continued, moving fast, talking loud, hoping the authority in his voice would somewhat rub off on these defeated people… The Jews finally caught on. They started groping in pockets for bits of identification. A driver’s license or birth certificate seemed to do the trick. The Swede was grabbing them so fast; the Nazis, who couldn’t read Hungarian anyway, didn’t seem to be checking. Faster, Wallenberg’s eyes urged them, faster, before the game is up. In minutes he had several hundred people in his convoy. International Red Cross trucks, there at Wallenberg’s behest, arrived and the Jews clambered on… Wallenberg jumped into his own car. He leaned out of the car window and whispered, ”/ am sorry,” to the people he was leaving behind. ”/ am trying to take the youngest ones first;” he explained. ”/ want to save a nation.” (Marton 110:11)

This type of action worked many times. Wallenberg and his aides would encounter a death march, and, while Raoul shouted orders for all those with Swedish protective passports to raise their hands, his assistants ran up and down the prisoners’ ranks, telling them to raise their hands whether or not they had a document. Wallenberg ”then claimed custody of all who had raised their hands and such was his bearing that none of the Hungarian guards opposed him. The extraordinary thing was the absolutely convincing power of his behavior,” according to Joni Moser. (quoted in Bierman 90)

Wallenberg indirectly helped many who never even saw his face, because as his deeds were talked about, they inspired hope, courage, and action in many people who otherwise felt powerless to escape destruction. He became a symbol of good in a part of the world dominated by evil, and a reminder of the hidden strengths within each human spirit.

Tommy Lapid was 13 years old in 1944 when he was one of 900 people crowded 15 or 20 to a room in one of the Swedish safehouses. His account illustrates not only vintage Wallenberg tactics, but also how Wallenberg epitomized hope and righteousness, and how his influence extended throughout the land as a beacon to those engulfed in the darkness of despair.

”One morning, a group of these Hungarian Fascists came into the house and said all the able-bodied women must go with them. We knew what this meant. My mother kissed me and I cried and she cried. We knew we were parting forever and she left me there, an orphan to all intents and purposes. Then, two or three hours later, to my amazement, my mother returned with the other women. It seemed like a mirage, a miracle. My mother was there–she was alive and she was hugging me and kissing me, and she said one word: ”Wallenberg.” I knew who she meant because Wallenberg was a legend among the Jews. In the complete and total hell in which we lived, there was a savior-angel somewhere, moving around. After she had composed herself, my mother told me that they were being taken to the river when a car arrived and out stepped Wallenberg–and they knew immediately who it was, because there was only one such person in the world. He went up to the Arrow Cross leader and protested that the women were under his protection. They argued with him, but he must have had incredible charisma, some great personal authority, because there was absolutely nothing behind him, nothing to back him up. He stood out there in the street, probably feeling the loneliest man in the world, trying to pretend there was something behind him. They could have shot him then and there in the street and nobody would have known about it. Instead, they relented and let the women go.” (Bierman 88-89)

Virtually alone in the middle of enemy territory, outnumbered and outgunned beyond belief, Wallenberg worked miracles on a daily basis. His weapons were courage, self-confidence, ingenuity, understanding of his adversaries, and ability to inspire others to achieve the goals he set. His leadership was always in evidence. The Nazis and Arrow Cross did not know how to deal with such a man. Here was someone thickly cloaked in apparent authority, but utterly devoid of actual political or military power. Here was a man who was everything they wished they could be in terms of personal strength of character, but for the fact that he was their polar opposite in purpose.

It is impossible to calculate precisely how many people Raoul Wallenberg directly or indirectly saved from certain death. Some estimate the number saved as close to 100,000, and countless more may have survived in part because of the hope and determination they derived from his leadership and example. (House of Representatives Report, Ninety-Sixth Congress, 2-3). Additionally, he inspired other neutral embassies and the International Red Cross office in Budapest to join in his efforts to protect the Jews. But the desperate days just prior to the Soviet occupation of Budapest presented Wallenberg with his greatest challenge and most astonishing triumph.

Eichmann planned to finish the extermination of the remaining 100,000 Budapest Jews in one enormous massacre; if there was no time to ship them to the death camps, then he would let their own neighborhoods become their slaughterhouses. To cheat the Allies out of at least part of their victory, he would order some 500 SS men and a large number of Arrow Cross to ring the ghetto and murder the Jews right there. Wallenberg learned of this plot through his network of contacts and tried to intimidate some lower-ranking authorities into backing down, but with the Soviets on their doorsteps, many ceased to care what happened to them. His only hope, and the only hope for the 100,000 surviving Jews, was the overall commander of the SS troops, General August Schmidthuber.

Wallenberg sent a message to Schmidthuber that, if the massacre took place, he would ensure Schmidthuber was held personally responsible and would see him hanged as a war criminal. The bluff worked. The slaughter was called off, and the city fell out of Nazi hands soon thereafter when the Soviet troops rolled in. Thus, tens of thousands were saved in this one incident alone.

But while peace came to Europe, Wallenberg’s fate took a very different path. He vanished, and the whole truth of what happened to him has not been revealed even to this day [Editor’s note: See addendum to this case]. From various sources, though, the following seems to have occurred.

The Soviets took Wallenberg into custody when they occupied Budapest, probably because they suspected him of being an anti-Soviet spy. For a decade, they denied any involvement in Wallenberg’s disappearance. Then they admitted having incarcerated him, but claimed he died in prison of a heart attack in 1947, when he would have been 35 years old. Since then, however, many people who have served time in Soviet prison have reported seeing Wallenberg, conversing with him, or communicating with him through tap codes. Others have heard of him and his presence in the prisons, but had no direct contact. The Soviets have denied the accuracy of all of these reports and have never deviated from their official position. But in 1989, Soviet officials met with members of Wallenberg’s family and turned over some of his personal effects. Reportedly, a genuine investigation was launched in an effort to determine the truth. Whether the years and the prisons will ever yield up their secrets remains to be seen.

In Israel there is today a grove of trees, planted by the Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, or Yad Vashem. Known as The Avenue of the Righteous, each tree memorializes a ”righteous Gentile,” someone who risked his or her life to help Jews during the Holocaust. The trees stand in silent testament to those who, in the words of a former speaker of Israel’s parliament, ”saved not only the Jews but the honor of Man” (Bierman viii). Along with Raoul Wallenberg’s tree, there is a medal. His medal bears the language of the Talmud and summarizes his mission in the words, ”Whoever saves a single soul, it is as if he had saved the whole world.”

The chairman of Yad Vashem, Gideon Hausner, who also prosecuted Adolf Eichmann, summarized his feelings for Raoul Wallenberg in this way:

”Here is a man who had the choice of remaining in secure, neutral Sweden when Nazism was ruling Europe. Instead, he left this haven and went to what was then one of the most perilous places in Europe, Hungary. And for what? To save Jews. He won his battle and I feel that in this age when there is so little to believe in–so very little on which our young people can pin their hopes and ideals–he is a person to show to the world, which knows so little about him. That is why I believe the story of Raoul Wallenberg should be told and his figure, in all its true proportions, projected into human minds.” (Bierman viii-ix)

There is much we all can learn from Raoul Wallenberg’s life. Young and old alike need heroes, role models, people to remind us of the immensity of human potential for good in the midst of evil. The United States Congress recognized this when it made Wallenberg only the second person ever to be awarded honorary United States citizenship; the other is Winston Churchill. On that occasion, one television news commentator spoke for millions when he said, ”It is human beings such as Raoul Wallenberg who make life worth living.”

Leaders at every level can make use of Wallenberg’s life and example to enhance their ability to inspire, to motivate, and to succeed. Leadership is difficult to define, but ”you know it when you see it.” Looking at Wallenberg’s heroic work in Hungary one sees leadership in action. We will now more closely examine his leadership style. There are several elements of what we shall call ”The Wallenberg Effect” which can be adapted and incorporated into each leader’s own personal style and situation.

1. Knowledge

Wallenberg’s success was largely based upon knowledge–of his enemies, of resources available to both sides, of the limits as to what was permissible, and of himself. This information enables a leader to understand each situation within a context that will allow a reasoned course of action. This is why knowing the facts and the substantive details surrounding issues has always been and always will be an integral part of a leader’s decision-making and problem-solving ability.

The traditional types of information gathered, such as planned actions, location, movement, numerical strength, type and condition of circumstances, and availability of material resources are obviously important. But Wallenberg proved the utility of subtler information as well. Because he understood the way his enemies thought and felt, because he comprehended what motivated them, he knew which buttons to push in each individual situation. He knew the great deference to authority and the fear of those in positions of power that were part of the Nazi and Arrow Cross mentality. This enabled him to bluff them with his false passports and with his air of officialdom so as to achieve excellent, seemingly impossible results. Wallenberg had a commanding presence, which is a hallmark of the effective leader, but that presence was fortified with a knowledge of how he would be perceived by his adversaries.

He also understood the rules of the game he was playing, as they applied to him, his associates, and their opponents. In effect, Wallenberg was very much a situational leader. He was able to adapt his behavior to meet the demands of the unique circumstances that confronted him. This is why he demanded and obtained authority from the Allies to use deception, bribery, and threats, and to invoke Swedish immunity as needed. He was in an environment where such tactics were the rule rather than the exception; they worked for others, and he knew he could make them work for him. As a leader, Wallenberg was out front, not hiding behind a desk or behind bureaucratic inertia. He showed initiative. He responded to an obvious need with imagination and creativity. He understood what was involved and he fully accepted the consequences.

Finally, he knew himself. He had a grasp of his talents and weaknesses and how they fit in with those of his opponents. Thus, what he could not possibly have accomplished through military force or physical violence, he did through bravado, intimidation, and illusion. Any other tactics would have met with crushing defeat. This is not to imply that leaders should always behave in this manner. It simply suggests that these strategies employed by Wallenberg were essential to fulfill his objective under the most extraordinary of conditions, and that they were chosen with full comprehension of the alternatives and their consequences.

In essence, the Wallenberg Effect suggests that becoming a mature leader means first becoming yourself, learning who you are and what you stand for. Implicit in this notion is the theory of self-discovery, getting in touch with oneself. Wallenberg teaches us that to grow as a leader involves reflecting on oneself, putting values in perspective, thinking about the task to be accomplished and influencing others to get the job done. Wallenberg’s work in Hungary is a testimony that leaders are foot soldiers who battle for the ideals in which they believe, and that leadership has far less to do with using other people than with serving other people. Plato said that ”man is a being in search of meaning.” In essence, servanthood is the key to successful leadership, which in turn can result in meaningful accomplishments. Raoul Wallenberg found himself and the meaning of his life by losing it in the service of others.

The process of learning about oneself and others, on an in-depth level, requires hard work. It is not something that can be gained solely from book study. It evolves best through personal introspection, human interaction and feedback, and through life experiences, observations, and analysis. It involves large quantities of common sense and realistic perspective. But its yield is high; it pays big dividends to those leaders who spend the time and make the extra effort to go beneath the surface, to discover what makes a person tick, because life and its activities are all part of the human experience. At bottom, it is all a matter of people, and the leader who understands people is prepared to win.

2. Objective

Every leader must have a clear, specific objective in mind at all times, a destination towards which all actions are directed. When the leader says forward march, everyone must know where forward is. If the leader lacks a sense of direction, then the followers will wind up some distance from the goal, like explorers without a compass or a guiding star.

Closely related to objective is vision, which implies having an acute sense of the possible. All effective leaders possess this capacity; they are able to focus sharply on what is to be done, seeing the objective as if through a powerful telescope.

Wallenberg exemplifies the principle that a clearly defined objective is absolutely essential as the focal point of our energies. His work in Hungary suggests that effective leadership is not neutral nor sterile, but deeply emotional, and that leaders must hold a sense of mission, a deeply felt belief in the worth of their objective. Nothing less has the necessary power to motivate leaders or followers to stretch the limits of their abilities. Total commitment comes only from total conviction that the goal is significant and right.

This ethical sense of mission grows out of a lifetime of value-building study and experience. However, the Wallenberg experience teaches us that much can be done in a short amount of time to impart principles upon which a given objective is based. All leaders should study the great foundational works of their nation to learn of the struggles of prior generations, ponder them, make them part of their being, determine how they apply to the situation at hand, and then transmit key principles to followers. History and philosophy form the underpinnings of the way of life for which people live and die. If values are thought to be only relative, if there is no right and wrong, if one system of government is morally equivalent to all others, then there is nothing worth sacrificing for. The leader will be limited to appeals to local pride and self-interest in attempting to inspire excellence. The result will often be halfhearted effort–and failure.

3. Ingenuity

Where only unquestioning obedience is valued, and where only strict adherence to rigid procedures is allowed, inflexibility and predictability are the consequences. But to succeed as a leader, or even to survive in a constantly changing and dangerous environment, creativity and adaptability are essential. This is where leaders must apply their foundational knowledge to the objective at hand and develop solutions, even in situations where there is no textbook answer.

Wallenberg knew that he had virtually no tangible resources and few allies. He also knew the type of people who stood in his path. And so, out of scraps of paper and a surplus of courage and personal character, he intimidated and defeated seemingly invincible enemies, time and again. Nazi numerical superiority and force of arms were powerless when confronted with a man who knew their own game better than they did and who could think faster than they could.

Throughout his entire experience in Hungary, in all that he did, Wallenberg had the daring to accept himself as a bundle of possibilities, and he boldly undertook the game of making the most of his best. Wallenberg instructs us that the leader is not a superman, but simply a fully functioning human being. Successful leaders are aware of their possibilities. Erich Fromm said that the pity in life today is that most of us die before we are fully born. Leaders such as Wallenberg are not merely observers of life, but active participants. They take the calculated risks required in exercising leadership and experimenting with the untried. It is surprising (and most aspiring leaders do not realize it) but much failure comes from people literally standing in their own way, preventing their own progress. Wallenberg never blocked his own path; rather, he created new paths where others saw only impenetrable walls. And in the process he was able to motivate others to do the same. He was a dispenser of hope in an environment filled with hopelessness and despair.

History is replete with instances where small, militarily weaker forces triumphed on the strength of superior strategy and tactics. Ingenuity makes surprise possible and allows quick adaptation and reaction to an adversary’s actions. Without flexibility, humans are reduced to automatons, programmed only for failure.

Ingenuity requires information as its fuel. The established objective and the available tools and procedures provide the raw material for any leadership action. But much can be accomplished when leaders reach beyond traditional methods and use the status quo as a floor rather than a ceiling. Leaders must be evaluated on the basis of what they achieve. Results are what counts, not formulaic adherence to precedent. Wallenberg was an achiever; he was results-oriented. We, like him, can ”do more with less” when we think creatively and are not confined to what has already been done. Military leaders are often criticized for preparing to fight the previous war. The best leaders think of all the possible ways in which available resources might be used or modified to achieve the objective, as well as how the opposition might do the same. Who would have thought, for example, that silicon, common sand, would be the basis for the phenomenon of microcomputer chips and would revolutionize modern society? To see each problem from multiple perspectives is to multiply the possible solutions and open the door for victories that would be inconceivable under ”conventional wisdom.”

4. Confidence

Leaders create an environment in which ideas can flourish and see the light of day. To do this, leaders must be self-confident, and have faith in themselves and others. People in leadership positions need a solid sense of self. It serves them well in times of turmoil, which inevitably await those who aspire to lead. The way people feel about themselves affects virtually every aspect of their lives. Self-esteem, which emerges from a sense of confidence, thus becomes the key to success or failure. In effect, leaders such as Wallenberg defy the law of averages and win because they expect success from themselves.

An indispensable ingredient of Wallenberg’s success was an almost tangible self-confidence. He radiated certainty, composure, and authority, and this breathed life into his otherwise foolhardy actions. He compelled his enemies to accept as valid passports things such as library cards, laundry tickets, and even nothing at all … and he did it by infusing all of his actions with the sheer power of his personality. Through his aura of conviction he also inspired people who in many cases had already resigned themselves to execution to join in his actions and save themselves and others.

Some would argue that the elusive quality we call ”charisma” is a gift with which some people are blessed from birth. But even if this is true, everyone can cultivate a positive attitude and an air of self-confidence, within the bounds of his or her own personality.

This unique aspect of leadership tends to develop as a natural consequence from the qualities previously discussed. As leaders learn about themselves and their opposition, they identify their respective strengths and weaknesses and compose a creative strategy for bringing their own greatest assets to bear against their opponents’ most vulnerable areas. Wallenberg understood, as did Napoleon, that ”Strategy is a simple art, it is just a matter of execution.” When leaders act from a position of advantage, they feel confident that they will prevail … and this confidence will be perceived by friends and foes alike.

Further, the leaders’ actions will be focused on a purpose which the leaders believe to be right. This sense of the righteousness of the cause will also strengthen resolve. Conversely, where the leaders do not believe in the virtue of their actions, they will lack commitment and will be hindered by self-doubt. Such uncertainty will be apparent to others, undermining the confidence of the followers and encouraging their opponents. It will contribute to eventual defeat and failure.

Wallenberg teaches us that it is important for each leader to become convinced of the worthiness of the mission, on some deeply felt level. Even when the immediate objective seems questionable, the leader must find justification in some indisputable value, such as support of the nation’s honor. Then, that conviction must fortify all of the leader’s actions. Wallenberg is a clear example that when a leader exudes a quiet confidence, surety, and decisiveness, followers will be inspired and opposition will be weakened. Leaders have been described as ”strong,” ”powerful,” ”magnetic,” and ”charismatic.” But whatever else they may be, they certainly are self-confident, and from this confidence leaders are able to mobilize and inspire individuals and groups to make their own personal dreams and objectives come true.

5. Courage

When a sense of mission becomes powerful enough to motivate people to action, even in the face of personal danger or certain death, that is courage. To be courageous one need not be fearless; it is natural and good to be afraid when confronted with real risks. But so long as that fear does not paralyze, there is courage at work.

Wallenberg knew he was entering a lion’s den when he accepted his mission to Hungary. Innumerable times he ignored armed soldiers and even flying bullets to continue his rescue operations. He had the audacity to threaten high-ranking Nazi officers, who had proved their willingness to murder innocent civilians, let alone troublesome opponents, under conditions where they easily could have killed him. Although in constant fear for his life, he pressed on, risking and ultimately sacrificing himself for his mission.

Can courage be learned? It can, in the sense that the development of deep devotion to a cause galvanizes a person to act on behalf of that cause. This type of fundamental belief in the value of the mission is essential to the cultivation of courage.

If self-interest were the most important then self-sacrifice would be out of the question. Only a profound conviction that there is a good greater than self can spark a person to risk everything for others. Self-sacrifice, and the courage to take that chance, are the antithesis of ”me-generation” philosophy. When the lives or liberties of others are valued more highly than one’s own life, then true courage can provide the fuel for remarkable accomplishments.

Wallenberg’s life can help others form a series of constellations by which they can successfully chart their own contributions to humanity. A key element of what we call the ”Wallenberg Effect is this idea: Do not give in to life nor its challenges. Dig in! Accept responsibility and in the process make a difference.

To some people, life is like the weather; it just happens to them. But to those who display the Wallenberg Effect (heroic leadership under adverse conditions) life is a great journey in human accomplishment. Wallenberg, like the trees of the Avenue of the Righteous, stands tall in the annals of man’s ”humanity” to man.

Few leaders will ever have the opportunity to help as many people as did Raoul Wallenberg. Still, each victory is immeasurably precious for those whose futures are spared. They, their children, their grandchildren, their entire posterity, and all whose lives will be touched by them, owe their existence to that one heartbeat of time when a person took action, despite the dangers. Although conditions may differ, the lessons for leadership that the Wallenberg Effect demonstrates should be valuable for all who aspire to more effective Leadership. With patient application, it can be transferred and applied to everyday leadership problems, whether on the level of nations or individuals. As Wallenberg’s medal testifies, ”Whoever saves a single soul, it is as if he had saved the whole world.”

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND IDEAS

- What do you think motivated Wallenberg, a wealthy, young, non-Jewish civilian citizen of neutral Sweden, to risk his life for the endangered Hungarian Jews? What motivates you in the duties you perform? Why are you in the occupation you now pursue?

- What enabled Wallenberg to inspire, in those he helped, a belief in the possibility of success and a willingness to try, in the face of hopelessness and resignation to defeat? Have you ever known leaders who could cause positive transformations in the attitude of the people under their care? How did they accomplish this? What effect have you had on the attitude of the people you lead? Why?

- How could Wallenberg, who had no weapons and little if any official status or power in Nazi-occupied Hungary, induce his Nazi and Arrow Cross enemies, including their highest ranking officers, to do his bidding? Have you ever faced a situation in which you had to ”do more with less” and tackle a problem with seemingly inadequate resources? What did you do? What were the results?

- Was it morally wrong for Wallenberg to use deception, threats, and bribery in furtherance of his mission? Compare and contrast his situation with examples from your experience in which you were tempted to ”bend the rules.”

- Consider the following two sentences. Which comes closer to your own personal view? Why? For what, if anything, would you be willing to risk your life? Why?

- ”Nothing is worth dying for.”

”If nothing is worth dying for, nothing is worth living for.” - How would you define the word ”hero?” What qualities or feats constitute heroism? Have you known anyone you consider to be a hero? To what extent is heroism important to your life and career?

- Can leadership be taught? How do you identify potential leaders? What sets leaders apart from other members of an organization?

- How can you incorporate the Wallenberg Effect into your work?

- How would you rate Wallenberg as a leader? Why?

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

Anger, P. With Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest. Holocaust Library (NewYork), 1981.

Bennis, W. On Becoming a Leader. Addison-Wesley (Reading, MA), 1989.

Bennis, W. and Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge. Harper and Row (New York), 1985.

Bierman, J. Righteous Gentile. Viking Press (New York), 1981.

Greenleaf, R. Servant Leadership. Paulist Press (New York), 1981.

Hersey, P. and Blanchard, K. Management of Organizational Behavior. Prentice-Hall (Englewood Cliffs, NJ), 1988.

Human Rights in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Committee on Foreign Affairs and Subcommittee on International Organizations, House of Representatives, Ninety-Sixth Congress, U.S. Government Printing Office (Washington), 1980.

Lester, E. Wallenberg: The Man in the Iron Web. Prentice-Hall (New Jersey), 1982.

Lester, R., (Executive Editor), Concepts for Air Force Leadership (AU-24). Air University Press (Montgomery AL), 1990.

Marton, K. Wallenberg. Random House (New York), 1982.

Peters, T. Thriving on Chaos. Knopf (New York), 1987.

Rosenfeld, H. Raoul Wallenberg, Angel of Rescue. Prometheus Books (Buffalo), 1982.

Werbell, F. and Clarke, T. Lost Hero: The Mystery of Raoul Wallenberg. McGraw-Hill (New York), 1982.

Zalenznik, A. The Leadership Gap. The Washington Quarterly, 1983.

Addendum

Excerpt from USA Today, Thursday, March 21, 1991

WALLENBERG CASE:

The Soviet Union handed Sweden 70 hitherto secret documents on the case of missing Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. Wallenberg, who saved thousands of Hungarian Jews from Nazi death camps, disappeared after Soviet troops entered Budapest in the last days Of World War II. Swedish radio and the documents reportedly confirm a Soviet claim that Wallenberg died of a heart attack in a Moscow prison in 1947.

About the Authors:

John C. Kunich is an active duty Air Force judge advocate currently assigned to Headquarters Air Force Space Command at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs CO. He holds a Bachelor and Master of Science degree with highest honors from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He received his Juris Doctor degree cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1985, and his Master of Laws degree in Environmental Law, with highest honors, from George Washington University School of Law in 1993. He is married to Marcia Vigil.

Richard I. Lester is the educational advisor to the Ira C. Eaker College for Professional Development, Maxwell AFB AL. He has lectured at the Air War College, the Air Command and Staff College, the Naval War College, and the Naval Post Graduate School. He has also lectured at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Massachusetts, University of Connecticut, Holy Cross College, and the American Management Association. Dr. Lester studied at the University of London and completed his doctorate at the University of Manchester. He has published over 30 articles on a variety of subjects in both national and international journals.