NEW YORK CITY – The Board of the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation has resolved to pay tribute to the legacy of Rev. Asa Kent Jennings in a series of activities that will be made public soon.

Jennings was an American hero who saved 350,000 people in 11 days and 1,250,000 people in 10 months at the end of the Greek-Turkish War of 1919-22. Of the 350,000, there were 300,000 Greeks, 25,000 Armenians and 25,000 Jews. Despite his awe-inspiring life-saving deeds, his story has not been properly recognized, not only around the world, but also in the USA.

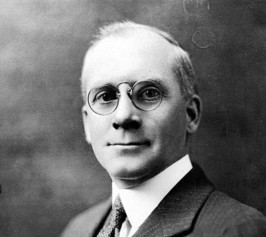

Asa was a Methodist minister from a small town in upstate New York near Rochester. In those days ministers frequently were also farmers, but Asa was a hunchback with only 45% breathing capacity as a result of Potts Disease, a form of tuberculosis. He took a job with the YMCA and arrived in the affluent city of Smyrna, Turkey, in August 1922. Two weeks later the Greek Army was defeated, panicked, and retreated to Cesme, Turkey, just beyond Smyrna. Fearing the Turks, the minority civilian Greeks and Armenians also retreated to Smyrna, but were left unprotected by the Greek Army that had left Turkey on ships.

Asa organized the American Relief Committee staffed by volunteer Americans who worked in local schools and businesses. The members gathered flour and fuel to make bread to feed up to 350,000 people per day. Wild, undisciplined Turkish brigands entered the City in advance of the Turkish Army. The brigands looted, raped, and killed at will. The weather was very hot, and there was no sanitation. Dead people and parts of people were everywhere. The stench was horrific. Women and girls were at the greatest risk, and there were many orphans whose parents had been killed by the brigands.

A wealthy Greek family that had the money to buy passage out of the City gave their house on the waterfront to Asa Jennings. He put 500 women in the house, and 2000 orphans out in front of the house protected by sailors of the U.S. Navy. He established a maternity ward in the house. Then Asa got more houses to protect more women from the unthinkable.

The Turkish Army entered the City on September 9, but did not attempt to stop the violence. The Greek Army had committed atrocities against the Turkish people and to the Turkish leadership retribution was in order. Much of that violence was against ethnic Greeks whose families had lived in Turkey for generations and were not part of the violence against Turks. The Armenians sought retribution against the Turks, and paid dearly. The Jews who had lived in the City were not contentious with the Turks and were not targeted by the Turks.

On September 13 the City burned to the ground. People jumped into the water to escape the fire and brigands. Many died. Ships of foreign navies only removed their own citizens. Greece did not send ships. The risk of disease breaking out was great. So the Turkish nationalist Government announced that everyone in the City would be marched to the interior of Turkey like the Armenians of 1914. Everyone knew that meant death.

Back in 1905 when Asa was in a Syracuse, New York, hospital suffering from Potts Disease there were 27 doctors who said Asa would only live a few more weeks. There was no hope or medicine for an infectious disease. Asa said that he could not die, because he had a great mission in life to accomplish, and he wanted to go to Jerusalem. On September 20, 1922, Asa was overcome by a great emotion, he later reported, to get ships, because only ships would saved these stranded people.

Asa drove his YMCA Chevy to the headquarters of the Turkish Army and got a meeting with the supreme Turkish leader Gazi Mustafa Kemal, later known as Ataturk. Asa convinced Kemal to allow these people to leave Turkey. Kemal imposed conditions, one of which was Asa had only 7 days to remove 350,000 people. Another condition was men of military age were not allowed to leave Turkey for fear they would return as an invading army. Most of those men expired in Turkey. The Turks had no ships. So Asa went to the port, boarded a US Navy destroyer, and received a boat with coxswain to take Asa to the Pierre Loti, a French ship. The French ship captain did not want to get involved and refused to take people to safety. So Asa went to the ship Constantinople. The Italian captain said he could take 2000 people, if he received a bribe. Asa, the minister, paid the bribe and 2000 people were put on the ship. Then the captain wanted more money. His excuse was the Greeks might not let these people off his ship, and he would have to travel a greater distance. Asa settled the dispute by saying he would go on the trip, and it would be his responsibility to get the people off the ship.

The ship went to the closest Greek territory, Mitylene on the island of Lesbos. There was no problem getting the people off the ship. At anchor were the Greek ships that had removed the Greek Army. Greek General Frangos would not let the ships be used to save the Greeks in Smyrna, Turkey. Later Jennings found out Frangos was part of a group planning a coup of the Greek Government and needed the ships and troops to implement the coup. Then the Greek battleship Kilkis (formerly the USS Mississippi) came into the harbor. Jennings boarded the Kilkis and found the commanding officer, Captain I. Theofanides, very willing to help. The Captain helped Asa blackmail the Greek Government to get 26 Greek ships placed under the command of Asa Jennings to remove the minorities from Smyrna. For his patriotic service to his country, Captain Theofanides was immediately kicked out of the Greek Navy, and Greeks today do not know of their great hero.

Asa had the American flag flying on the ships as they entered the Smyrna harbor to the cheers of the desperate refugees. These ships were protected by ships of the US Navy, and the sailors entered the City to protect as many people as possible from the brigands and Turkish Army. The US Navy was welcome in Turkey while all other navies were barred from Turkish ports. U.S. citizens had been helpful to the Turkish people during World War I even though the U.S. was technically at war with Turkey, and the U.S. unlike Greece, Italy, Russia, France and U.K. never claimed Turkish soil after World War I. The rescue was not completed after 7 days, and the Turks allowed the rescue to continue for the 11 days required to remove all of the minorities. Then Asa requested permission from Gazi Mustafa Kemal to remove all the minorities from all ports of Turkey from the Black Sea down to Syria. The fleet was expanded by Greece to 55 ships, and 10 months were required to remove 1,250,000 people.

Asa Jennings was a national hero in Greece. As he walked down the streets of Greece he was very recognizable by his hunchback and panama hat. The crowds would kneel as he approached out of respect like the Host being paraded down the street. People wanted to kiss his hands and feet, and being a humble person he was very embarrassed. People asked for assistance finding lost relatives. This was a heart wrenching experience for Asa.

Greece and Turkey were at war and hated each other. Both the Greek and Turkish Governments appointed Asa as their diplomat in common knowing he was representing the enemy at the Treaty of Lausanne. Asa’s responsibility was POW and population exchange. However, in Asa’s opinion his greatest accomplishment was not the rescue of 1,250,000 people or being the representative of warring countries, but rather the social work after the war. Both countries wanted his services. Greece was a modern western country of educated people with many friends around the world. Turkey did not educate its youth and was economically devastated. During the nearly 700 years of the Ottoman empire work was performed by the minorities, and Turks only served in the army or government. Once the minorities left Turkey, the Turks had to learn to work.

Jennings created The American Friends of Turkey, because the word Christian in YMCA was offensive to Muslims. The AFOT was funded mainly by Hoover of Hoover Vacuum in Canton, Ohio, and “Golden Rule” Nash, an insurance execute from Cincinnati, Ohio. Vocational training was started all over Turkey. The first day care center was created in Smyrna (Izmir today) so women would know their children would be safe while women worked in plants packing tobacco, olives and many other agricultural products. Previously, women stayed at home and were only seen by their children and husband. Gazi Mustafa Kemal wanted to build a prosperous country. The addition of women to the work force made a huge difference in the economic growth of Turkey and family income.

The first athletic field in Turkey was built and supervised by The American Friends of Turkey. Turkish men learned to compete in sports and shake hands at the end of the game rather than losers trying to kill the winners. The lesson was tolerance. In Islam, one does not lose. Then women started to compete in sports despite the claims of the mullahs that this was the evil influence of western culture like we hear in Iran today. The Gazi grew tired of the mullahs and shut down the mosques in Turkey and banished the mullahs. Koranic law was abolished and women were given equal rights. Education became mandatory. The Health Department of the City of Chicago provided written instructions how a new borne should be cared for. The American Friends of Turkey had these instructions translated into Turkish and distributed all over Turkey. The American Friends of Turkey built the Ucak Building in the capital of Ankara, and provided the livestock and seedlings for Gazi Mustafa Kemal’s model farm in Ankara.

The value of changes like these in Turkey is evident when one looks at the former Ottoman territories that did not have Asa Jennings instigating social change like Syria, Iraq, Egypt and the rest of North Africa. Modern day Turks are very different from Ottoman Turks and their likeness in the former territories.

Asa’s life shows that one person can make a difference.

The IRWF decision to commemorate the feats of Jennings are in the framework of the NGO’s research efforts aimed at discovering the brave women and men who reached out to the suffering.

The story of Asa Kent Jennings is told in detail in the book Waking the Lion written from original records by his grandson Roger L. Jennings.