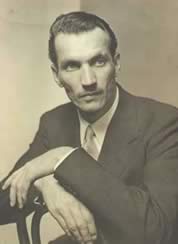

Jan Karski was born on April 24, 1914, in Lodz, Poland and died on July 13, 2000 in Washington DC. He belonged to a Catholic family and his studies were in charge of Jesuits, he studied Law at the University of Lwow and embarked on the diplomatic career. He took charges at the Bucharest, Berlin, Geneva and London embassies. He enlisted in 1939 and was captured by the Soviet army and placed in a Stalinist detention camp, from where he could escape to go underground. His fluency in several languages and his prodigious memory favored his election for becoming a courier for the Polish underground during the Second World War.

In 1940 he was captured by the Gestapo in Slovakia. After he was savagely tortured he tried to commit suicide by slashing his wrists, but the underground resistance could rescue him avoiding that any of the secrets he knew were revealed to the enemy. Between 1942 and 1943 he was the protagonist of a story that would mark him for the rest of his life: what he called ‘my secret Jewish mission’. Karski was one of the first ones to transmit a detailed narration of the Nazi atrocities.

In October 1942 Karski, whose real name was Jan Kozielewsky, contacted two Jewish organizations: the Bund (Jewish socialist party) and a Zionist organization. Both of them asked him to inform the allies about what was going on with the Jewish communities in Poland.

Pretending to be a Jew, he got into the Warsaw ghetto twice in October 1942. And afterwards, to the extermination camp of Belzec. Karski´s secret visit to the camp only lasted for an hour, which was more than enough for what he had seen to remain in his memory forever.

In London he had a meeting with the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Anthony Eden; with Lord Cranbone, of the conservative party as well as with Hugh Dalton and Arthur Greenwood of the Labour party. They were all part of the British cabinet of war that in that moment was the political center of power in England. Eden answered that they could not do anything of what the Jewish leaders proposed because the allied strategy consisted in defeating Germany militarily, and that no ‘secondary issue’ had to interfere with the objective. Lord Cranborne, apparently a nice man, told him:

‘Mr. Karski, you are a very bright man. Do you realize that the message you are giving us is untenable?’

Arthur Koestler, Jewish, passionate anti fascist and anti-Soviet whom Karski visited in London, is not favored in the messenger’s narration. He describes him as a man so tied down to his personal interests, to his vanity of man of arts. Another writer, H.G. Wells, when he received his chronicle answered:

‘there should be a study of what causes anti-Semitism to arise in every country where Jews live’.

The situation is not better in the USA. In the summer of 1943 he has a meeting with President Roosevelt, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, Cardinal Cicognani, Archbishop Spellman, the President of the Jewish-American Congress, Nahum Goldman, the Judge of the Supreme Court of Justice, Felix Frankfurter and with the director of the Herald Tribune, Ogden Reed. Roosevelt listened to him for four hours. He was especially interested in political issues and told him that Poland would receive a territorial compensation. Not a single comment about the Jews´ situation, not a single question that showed his worry about the ghetto chronicle and the extermination camps.

The dialogue with Felix Frankfurter, member of the Supreme Court, is equally clarifying. Frankfurter asked him: ‘Mr. Karski, do you know who I am? ¿Do you know that I am Jewish?‘ After Karski´s narration of the facts, Frankfurter walks a few steps, thinks for a while and answers him categorically: ‘A man like me has to be completely honest, so I tell you that I cannot believe what you are telling me’. Other Jewish leaders did not believe him either.

In 1944, a year before the war was over, Karski published the book The Secret State, that in a very short time sold 400 thousand copies, and he started lecturing in the USA, where he took as a Professor in Political theory at Georgetown University.

‘After the war -he wrote in 1987- I read how leaders from the west, State men, militaries, intelligence services, ecclesiastical authorities and civil leaders were horrified by what had happened to the Jews. They declared not to know anything about the Holocaust because the genocide had been kept in secret. This version of facts still remains but it is just a myth. The extermination was not a secret to them.’

The State of Israel named him honorable citizen. This time he gave a thank you speech where he defined himself: ‘I am Polish, American, Catholic and now I can also say that I am Jewish’. His testimony is probably one of the most touching registered on the movie Shoah by Claude Lanzmann.

For me, also born in Lodz, Jewish Polish, Jan Karski´s story is a reason of shudder and anguish: Why that man, that maybe I bumped into in the streets of my city, was not listened to? Why the testimony of an ordinary man had no effect, why that unbearable indifference?

On June 20, 2001 the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Argentina will remember the figure of Karski at the Embassy of Poland in Buenos Aires.

* By Jack Fuchs, Deported from the Lodzs ghetto to Auschwitz. He was found by the allies in Dachau at the end of the war. Member of the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation.