In the years before World War II, the members of the Nazi regime became intent on cultivating a sense of loyalty and entitlement in the German youth. It would be too late, they thought, to wait for adulthood; the Nazi mentality must be inscribed on children if it was to take hold and grow to support the cause. With such an intention, the Hitler Youth was born.

Though available to girls and boys (girls could join the Bund Deutsche Madel), the Hitler Youth was primarily interested in procuring control of Germany’s young males. Boys between the ages of 10 and 14 joined the Deutsches Jungvolk (German Young People) and those between 14 and 18 joined the Hitler Jugend, or Hitler Youth. At its peak, membership in the group totaled about 90 percent of the country’s eligible youth and was the world’s largest youth organization.

Both boys and girls were members of the Cologne resistance.

Both boys and girls were members of the Cologne resistance.The explanation for such a large enrollment percentage becomes clear when one considers that the Reich not only outlawed all other youth organizations, but also mandated Hitler Youth enrollment and even went so far as to threaten parents, telling them their children would be placed in orphanages if enrollment were denied. By the time the Nazis were done imposing restrictions, any youth group found together outside of a Hitler Youth association was considered criminal.

Initially, the Hitler Youth functioned much like any organization for young boys would. The boys played sports and games, hiked and went camping, all the while enjoying their small allowance of independence away from their families. With time, however, the Hitler Youth became more a method of recruitment and the organization increased its military training, leaving a great number of its members bored with their lack of freedom (they were supervised by older members who were divided into police squads), and dissatisfied with their activities, which once consisted of athletic games, but now included such enterprises as marching, drilling on the proper use of bayonets, grenades, and pistols, and maneuvering through dugouts, trenches and barbed wire. Pursuits also included stealing, vandalizing, fighting and bullying. (Because of a rule that disallowed police from arresting members of the Hitler Youth Patrol Service for their criminal activity, all was done without the fear of consequence.) Soon, these organizational changes led to an awakening regarding the actual motives behind the formation of the Hitler Youth.

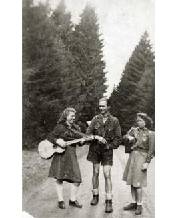

Cologne Navajos, around 1937

Cologne Navajos, around 1937Dissatisfied with the increasingly transparent purpose of the Hitler Youth and the loss of any freedom or fun which membership originally offered, a number of young boys and girls began looking for a way in which they could avoid association with the group altogether. Some did so by leaving school, which was permissible (and often the norm among children of working-class families) at the age of 14, or dropping out of the Hitler Youth, which, it must be remembered, was compulsory. If found they faced severe consequences. Nevertheless, in the period just before World War II, small groups (between 10 and 15 members), consisting primarily of boys between the ages of 14 and 18, began seeking each others’ company outside of the Hitler Youth.

Such groups began forming in the larger cities of Nazi Germany like Hamburg, Leipzig, Frankfurt and especially in Cologne, and identifying themselves with titles like ‘swings,’ ‘packs,’ ‘cliques,’ or ‘pirates’. The Farhtenstenze, or Traveling Dudes, for instance, came from Essen, the Kittelbach Pirates from Oberhaussen and Dusseldorf, and the Navajos from Cologne. Together, the members of these groups are thought to have totaled more than 5,000, about 3,000 in Cologne alone, and although each group maintained a separate identity due to its location, all considered themselves Edelweiss Pirates.

Named for the metal Edelweiss pins and badges members wore on their collars or hats, these working-class teens became ”one of the largest youth groups who refused to participate in Nazi youth activities,” says Sally Rogow, docent of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. In addition to their identifying pins, their long hair, style of clothing (usually colorful, checkered travel shirts and short, dark trousers or Lederhosen, white stockings and neck scarves), and the songs they played and sang (most contrasted greatly from the German Volkish music approved by the Nazis, were by Jewish composers or were anti-Nazi in theme), were all disallowed in the Hitler Youth and served to further distance them from the group. Individual groups of Edelweiss Pirates got together in cafes, parks, or street corners in the evenings or weekends, took hikes, rode bicycles into the country for camping trips, or traveled into neighboring towns to visit fellow Pirates. It must not be forgotten that such pastimes, when taken out of context, seem exceptionally harmless. Outside of the Hitler Youth, however, they were considered criminal activities and often resulted in serious ramifications.

The Pirates usually held jobs in mills or factories, but were eventually branded as being lazy in their work ethic and as nothing more than social outcasts. Due to their similar backgrounds and common environments, and because of their small numbers, they did feel a great loyalty toward each other and often had no friends outside of their Pirate comrades. The small percentage of teens who did not join the Hitler Youth were ostracized by Hitler Youth members, however, so it was not as if the cause for the Pirates’ perceived anti-social behavior was solely one-sided. Further, they must not be mistaken for ”deprived children or delinquents,” Rogow is careful to note. ”They were simply the sons and daughters of working class parents” and too young for the military. They did have rough pasts though; a number were without parents who, because of their communist views, had been either arrested or murdered. Others were left without fathers who were away fighting in the war.

Jean Jülich (right, with guitar) and his fellow Edelweiss Pirates

Jean Jülich (right, with guitar) and his fellow Edelweiss PiratesAs the war progressed, so did the seriousness of the activities in which the Edelweiss Pirates participated. Pirates in Cologne ”offered shelter to German army deserters, escaped prisoners from concentration camps and escapees from forced labor camps,” says Rogow, while others ”made armed raids on military depots and deliberately sabotaged war production.” Still others played pranks on the Nazis. Julich recalls how he and his friends threw bricks through munitions factories and poured sugar water into the petrol tanks of Nazis’ cars. Other Pirates vandalized city walls, spray painting them with lines such as ”Down with Hitler” or ”Down with Nazi Brutality.” Some stole, looting food and supplies from stores or freight trains, or derailed train cars full of ammunition and supplied adult resistance groups with explosives. Pirates from different towns would ”meet in the countryside, to swap information gained from illegally listening to the BBC World Service, or to plan leaflet drops in each other’s towns so the local police would not recognize them,” Hannah Cleaver of The Daily Telegraph (London) says. Leaflets contained allied propaganda or encouraged German soldiers to quit their fighting and return to their families.

In an interview, Walter Mayer, a member of the Edelweiss Pirates at the age of 16, recalled getting together with fellow Pirates at a cafe in Duesseldorf and playing pool. A member would ask, ”’What are we going to do next?’ and maybe one would say, ‘You know the Hitler Youths? They all store their equipment at such-and-such a place. Let’s make it disappear.’ ‘Okay, when are we going to meet?’ Such-and-such a time. And that’s what we did…You know we started maybe by deflating the tires. Then we made the whole bicycle disappear, so it came to the point where [there were] too many complaints.”

Jean Jülich

Jean JülichEdelweiss Pirates usually did their best to avoid the Hitler Youth Patrol, who were continually on the lookout for Pirate members, but some did provoke fights (one motto, after all, was ”Eternal War on the Hitler Youth”), attacking their enemies (guns were used on several occasions), and taking pride in their wins, which were not uncommon. ”We were not against the Hitler Youth,” Pagaard cites one Pirate as saying, however. ”We only wanted the Hitler Youth to leave us alone.” This was a viewpoint echoed by more than a few members.

Pirates who were caught could expect to face any number of various consequences. At the least, captured Pirates were threatened, beaten, or subjected to a head shaving, one of the most popular methods of humiliation. Pirates were also put in jail, sent to reform schools, psychiatric hospitals, or labor, reeducation or concentration camps. Some others were simply killed.

Jean Jülich (center) survived the Nazi purge on the Pirates.

Jean Jülich (center) survived the Nazi purge on the Pirates.At the age of 15, Pirate Julich was arrested with a number of others, tortured and imprisoned for four months. Julich’s friend and fellow prisoner and Pirate, Bartholomaeus (Barthel) Schink, a member of the Ehrenfelder Navajo Group, was publicly hanged on the gallows in Ehrenfeld, Cologne on the morning of November 10, 1944. ”The cause of Barthel Shink’s hanging was his membership in the Edelweiss Pirates,” Julich explains. ”And it is true that he planned to blow up a Gestapo building in Cologne with Hans Steinbruck.” But Schink, he adds, never killed anyone. Schink was hanged, without trial, as a criminal along with seven adults and five other teens and Pirates, of which, he was the youngest.

In 1988, the Edelweiss Pirates were recognized as ”Righteous among the Nations” by Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, but it was not until 2005, at the continued urging of Julich and Pirate Gertrud Koch that the group was ”politically rehabilitated,” the criminal status deemed them by the Gestapo was dropped and they were officially recognized as ”resistance fighters” and heroes. ”We were from the working classes. That is the main reason why we have only now been recognized,” Koch, 81, told reporter Cleaver. ”After the war there were no judges in Germany so the old Nazi judges were used and they upheld the criminalisation [sic] of what we did and who we were.” Koch, incidentally, ”still goes by her Edelweiss codename of Mucki,” reported Cleaver and is noted as mentioning of the Pirates, ”There are only five of us left in Cologne. Four of the boys and me.”

The story of the Edelweiss Pirates is slowly gaining its due acknowledgement. Julich has published his memoirs and contributes to various means of affording the Edelweiss Pirates their earned recognition. He supported the release of the 2005 German film, Edelweiss Pirates, which was dedicated to Schink and two other teens, hailing them as ”true heroes,” and his beautiful voice can be heard in a recent recording of ”Es War in Shanghai,” a popular Pirate song. ”’Es war in Shanghai’” was a romantic song the Pirates sang at campfires,” Julich explains. ”It was not a political song, but it addresses the desire for foreign countries, fellowship and independence. The Nazis did not sing this song because it was not consistent with their ideology.”

The very fact that the Pirates had cultivated their own ideology was meaningful enough to spur them to action and strong enough to support them in withstanding the cruelties it entailed, is more than impressive. Perhaps it was because of their youth that the atrocities of the Nazi regime were so clear and the choice to oppose it so absolute. Their decision was one of resistance and, consequently, was not without hardship, but it was also one of liberty, for, as one of their songs contends, ”Our song is freedom, love and life, / We’re the Pirates of the Edelweiss.”

References

- http://hometown.aol.com/baronvanc/swingyox.htm

- http://libcom.org/library/edelweiss-pirate-interview

- http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/n/a/2005/04/23/international/i110336D68.DTL

- http://web.lexis-nexis.com/universe/document?-M=4b67d8cc1046c806a241eaa15c2b36f3&_docnu…

- http://www.cooldictionary.com/words/Barthel-Schink.wikipedia

- http://www.cooldictionary.com/words/Edelweiss-Pirates.wikipedia

- http://www.deutsche-welle.de/dw/article/0,1564,1391096,00.html

- http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ht/38.2/pagaard.html

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/hitler_youth.htm

- The History Place

- Holocaust Teacher Resource Center: Faces of Courage: Teenagers Who Resisted

- Jewish Virtual Library: Hitler Youth

- http://www.libcom.org/history/articles/edelweiss-pirates/index.php

- Jean Jülich : Es war in Schanghai

- Interview with Jean Julich via Bernd Rademacher. Rec. 6 August 2006.