Bernardo Jerochim struggles to recover the German nationality which he lost 65 years ago due to a Nazi decree.

”I want my three sons to be German”, Bernardo says while he is watching out for some customer.

It was of no use for the Jerochims to have been settled in Prussia for generations; or that Michaelis Gerson Jerochim, head of the family, would have fought in World War II, that he would have been wounded four times, and that the Emperor would have bestowed on him the Iron Cross. The Jerochims used to live in Berlin, where Bernard was born on January 16th , 1925; but they were Jewish, and that was enough reason for Hitler’s regime to disdain them, as it was established in 1935 laws. Life was becoming really tough and a policeman forewarned Michaelis that things would be worse.

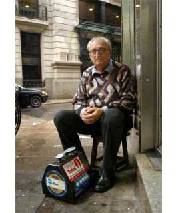

”I don’t recall anything about that day; with age memories tend to become vague”, Bernard, today called Bernardo, remarked. He is a shoeshine man who works in the city center of Buenos Aires. Although he does not recall exactly, he manages to describe how the family packed their suitcases one June morning in 1938, traveled to Hamburg and transferred by ship from there to Buenos Aires. Despite the fact that they had lost everything, they were lucky; they narrowly escaped with their lives. On July 23rd, the Nazi government decreed that all the Jews living in Germany should compulsorily sign in on a register.

”I have never obtained the Argentinian nationality”, Bernardo declares while he is watching out for customers. However, he was no longer legally German. On November 1941, the Nazis proclaimed that German Jews ceased to be German and this mandate has never been abolished. Bernardo, soon deprived of father and school, was too busy maintaining his mother and his five brothers. ”Then I got married and had three children”. Denied of nationality, in 1975 he began to go through the formalities to request for his nationality back, but bureaucracy proved to be inflexible. To complicate matters further, Michaelis, the man regarded as a heroe by the Reich II and regarded with disdain by the Reich III, had been born in Schneidemuhl, in Prussia, which at that time was called Pila, and it belonged to Polish territory. Consequently, it turned out to be very difficult for him to prove that his father had been German.

Bernardo is 79 years old; he does not work twelve hours a day anymore – ”I only work eight hours, from nine a.m. to to five p.m.; my son picks me up in his car”-, since he does not enjoy being in the streets for much time. He visits companies and offices where he has regular customers. Three years ago, in one of these places he met Alejandro Cardioti, an attorney who showed interest in his case. ”Bernardo used to stop by the offices and say: Shoe shine, shoe shine”. ”One day I mentioned that I had lived in Germany when little and he told me then that he was from Berlin”, he recalls.

The attorney became increasingly interested in the case of the shoeshine man, so he helped him to compile material information and to take steps to submit his case before the German Consulate in Buenos Aires and the Berlin Mayor’s Office. In spite of the proper handling, the nationality affair still was stuck; until one conversation changed the course of the case. Alejandro’s father, Enrique Cardioti, -at that time Argentine ambassador to Germany- mentioned Bernardo’s case during a conversation with Baruj Tenembaum, president of the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. This organization is named after the Swedish diplomat who saved the lives of thousands of Jews during the World War II and who disappeared after the Soviet Union. Tenembaum points out: ”If there was a decree that deprived Jews of citizenship, why wasn’t there another one to abolish it?”. He asserts that the existence of cases such as the one of the shoeshine man ”may be misconstrued, despite the good intentions of the German government”

”I have three sons and I want them to be German”, Bernardo claims while he watchs out for customers in a coffee shop. Finally, the formalities will de completed and his file closed by next June. He will have recovered the citizenship that Hitler’s laws deprived him of.

He narrowly escaped with his life. He has not seen many of his relatives for a long time. Unfortunately, he will not be able to see his brother, Werner, who passed away this week in Berlin.

Translation: Florencia Gersberg