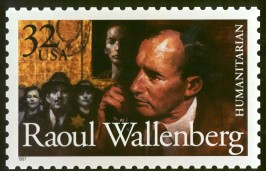

The U.S. Postal Service issued April 24 a stamp commemoration World War II hero Raoul Wallenberg. (Reuters)

The U.S. Postal Service issued April 24 a stamp commemoration World War II hero Raoul Wallenberg. (Reuters)On October 27, Swedish tax authorities issued a formal death certificate for Raoul Wallenberg, acting on a request by his family to settle his estate.

One would have liked to see the sad and uncomfortable burden of declaring Raoul Wallenberg dead shifted to others. For more than 70 years, the Russian government has refused to clarify the mystery of Wallenberg’s disappearance. The Swedish government, meanwhile, could have used the occasion to properly honor a man who, as their serving diplomat, saved thousands of Jews in war torn Budapest, only to be unceremoniously abandoned by his home country.

Much has been written about Raoul Wallenberg. The real person has remained somewhat elusive and literally two-dimensional, however — the public knows him only from a half dozen black and white photographs. Wallenberg left no tangible inheritance in Sweden, very little correspondence, no publications, no wife or child, or even close friends.

Instead it was his actions in Nazi-occupied Hungary in 1944 that resonated with the world.

In recent years, some historians have questioned the true effectiveness of his rescue efforts on behalf of Hungary’s Jews: how many people he really managed to save, and if he became famous mainly because he disappeared.

One could certainly argue that Wallenberg’s humanitarian mission to Budapest in the summer of 1944 was little more than a small ray of light in an otherwise disastrous failure to stem the tide of the Holocaust. Raoul’s mission, backed by the United States and the Swedish government, was conceived late, and haphazardly at best.

Yet in the hell that was Budapest in the second half of 1944, it is indisputable that Wallenberg made a huge impact. His efforts managed to protect, house and feed many of the close to 200,000 Jews left in the city. He was helped by the Hungarian resistance and the diplomatic representatives from other neutral countries, but it was a task that required an almost super human effort, one that tested every ounce of Raoul’s resourcefulness and strength.

Some analysts correctly point out that Wallenberg’s success was made possible largely because by the end of the war, the Quisling Hungarian government wished to accommodate international opinion. Still, this was a small opening, and it took great courage and commitment to take advantage of it.

What Raoul brought to Budapest was the idea of possibility, the idea that rescue was possible. Wallenberg’s official status as diplomat of a neutral country enabled him to be effective, and he had the help of many people who have not received adequate credit. But Wallenberg inspired those around him and that will always remain his greatest accomplishment.

It was this attitude that turned a small Swedish protective effort into an extensive rescue operation. And it is precisely this spirit that makes Raoul Wallenberg so special and so rare. He showed us that if we want to protect our core values as human beings, if we want to counter horrendous crimes like genocide, every one of us needs to take a stand.

How many of us would today consider packing our bags and going off to Mosul or Aleppo? Activism all too frequently imposes a brutal price on those who dare to speak out. Unfortunately, Raoul himself was no exception.

While Wallenberg’s achievements are unique, his legacy as a victim is much harder to define. In Russia alone twenty million people died during World War II. About twenty million more perished in the Gulag. Today, untold numbers of people all over the world endure horrendous human rights abuses.

With so much suffering, should one continue to insist on the truth about one man who disappeared 71 years ago?

The international jurist Thomas Buergenthal, himself a survivor of Auschwitz, answers this question with a resounding “yes”.

“Six million Jews means nothing. If you want to have an impact, talk about one person,” he says.

The search for historic truth, then – however arduous and ‘idealistic’ it may seem – is not just a laborious exercise but a vitally important process. Together with remembrance, it is the key step that allows us to learn from history.

The Spanish writer Miguel Cervantes once said: “In order to attain the impossible, one must first attempt the absurd.”

Raoul Wallenberg’s relatives certainly understand what Cervantes meant. The search for answers has been draining, and has exacted a serious financial and emotional toll. The family was forced to fight a two front battle, largely by themselves, over seventy years — against a lethargic Swedish government at home and an intransigent Russian leadership abroad.

Last month, a group comprised of Raoul’s family and Wallenberg experts returned to Moscow with a comprehensive catalogue of open questions and pending research requests to Russian authorities. They communicated the belief that the Wallenberg case could almost certainly be solved if Russian officials granted unhindered access to specific documentation that currently remains classified.

If the Russian government once again does not comply with these requests, the family is prepared to explore legal options.

In doing so, Raoul Wallenberg’s family and international researchers are broadening the traditional parameters of historical inquiry and investigation. The Wallenberg case has thus acquired once again an urgent relevance for a new generation of historians, activists and families seeking justice.

It is a worthy legacy indeed for a man who so fearlessly lead the way on behalf of fellow human beings more than seventy years ago.

Susanne Berger is the founder and coordinator of the Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative (RWI-70)

Dr. Vadim Birstein has published many articles on the Wallenberg case and is the author of the books The Perversion of Knowledge: The True History of Soviet Science (2001) and SMERSH, Stalin’s Secret Weapon: Soviet Military Counterintelligence in WWII (2012), which received the inaugural St. Ermin’s Intelligence Book Award in 2012