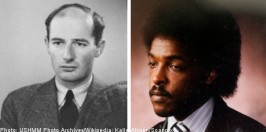

With Swedish journalist Dawit Isaak in prison in Eritrea and questions still swirling about the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, historian Susanne Berger argues that Sweden needs to do more to shorten its ignominious line of unsolved disappearances.

It has now been ten years since a joint Swedish-Russian Working Group presented its report on the fate of Raoul Wallenberg in the Soviet Union following his arrest by Russian troops in Budapest in January 1945.

Not surprisingly, relatively little progress has been made since the case moved from an official investigation to a subject of historical inquiry. We know crucial documentation is available, but we are not allowed to see it, nor do we get adequate official help from the Swedish government to obtain access to it.

Nevertheless, there have been some important breakthroughs since 2001. We do understand now that Russian officials intentionally withheld information from documentation presented to the Working Group as early as 1991, when the group began its work.

The documents were censored not primarily out of concern for Russian secrecy and privacy laws (that issue could have been easily circumvented), but clearly to prevent Swedish officials from learning information that would have led them to question the longtime Soviet version of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate, namely that he died of a heart attack on July 17, 1947 in Lubyanka prison.

The censored material would have shown that with great likelihood Wallenberg was interrogated by Soviet Security officials six days later, on July 23, 1947. If such information had been received in 1991, it might have set the whole inquiry of the Working Group on a different path.

The actions of the Swedish side also leave a few question marks. For example, in 1997 Russian officials informed the Working Group that Russian Foreign Ministry archives contain a number of secret coded telegrams which make direct reference to Raoul Wallenberg, although the Russians claim they include no information about his fate.

For that reason, Swedish officials agreed not to insist on a review of the documentation. Fifteen years later, the cables still have not been released. The same is true for a wide range of investigative files and other documentation from Russian intelligence archives that have remained completely inaccessible to researchers.

Historically, the unsolved cases of other missing Swedes have suffered from similar problems. These include the disappearance of a DC-3 with an eight-man crew on a reconnaissance mission over the Baltic sea in 1952 – four men remain unaccounted for – as well as questions about the fate of about the one hundred Swedish sailors who disappeared without a trace in the years 1946-1981 while travelling the dangerous coastal route between Sweden and communist Poland.

It further includes a number of Swedish citizens as well as foreign citizens who agreed to spy for Sweden during the Cold War in the Baltic nations and other iron curtain countries. Some of these individuals have never been publicly identified.

All these cases face serious obstacles preventing a full resolution: layered secrecy, fading memories, and the increasing urgency of present day matters. However, the growing disconnect with the past comes at a price.

We are currently witnessing some of the associated consequence of this failure right in front of our eyes. Swedish journalist Dawit Isaak is suffering his tenth year in captivity in Eritrea where he is held without official charge or trial. He is well on his way to joining the ignominious line of unsolved disappearances, with no solution in sight. It will not be long before there will be quiet, regretful calls to accept that he cannot be saved.

To be fair, diplomacy is often a thankless task. However, the available options for action are often not as limited as portrayed by professional politicians. Sweden has a long history as an arbiter of diverse interests and as such, it has a wide range of contacts to draw on.

Also, functioning democracies – as distinct from authoritarian regimes – voluntarily embrace standards of conduct which explicitly demand transparency to protect the rights of individuals. If those are ignored or relativised, we embark on a slippery slope.

As regards the core issue, the safeguarding of human rights, we have come a long way since the end of World War II, but two fundamental challenges remain: first, the legal status of human rights continues to be precarious. In spite of impressive progress, we still face serious hurdles when it comes to enforcement aspects, as the Dawit Isaak case graphically illustrates.

Secondly, this ambiguity is enhanced by a fast moving global economy which places a premium on pragmatist deal making in the fight to stay one step ahead of competitors, while struggling to accommodate the demands of a supposedly principled political agenda.

Regarding the issue of missing Swedes in the Cold War era, strategic compromise – driven by both pressing need and inherent tendency – appears to have guided Sweden’s approach over the years. For as yet undetermined reasons, in these discussions the Swedish government has often failed to take advantage of serious investigative options on the table, leaving both researchers and the public wondering as to the reasons why.

Now that Russia has essentially achieved its decades-long quest for membership in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), obtained in part through Swedish mediation, it will perhaps be more inclined to reveal additional information on historical issues. Sweden would do well to show a bit more muscle when it insists that the men who disappeared have an intrinsic value to the country that time cannot change.

It would be a great tribute to the spirit of Raoul Wallenberg whose 100th birthday will be celebrated in 2012 and whose rescue mission to Budapest rested on the very premise that there are things worth fighting for – namely people’s lives – no matter how uncertain the outcome.

Sweden’s approach to Eritrea and the Dawit Issak case should be equally clear cut. Unfortunately one does not get the sense that the Swedish Foreign Ministry is firing on all cylinders in this question either.

It should take its cues from past experiences. When diplomats talk only about the things they cannot do and why they cannot do them, it is generally a very bad sign. For Dawit Isaak today the past of his fellow vanished Swedes is casting a very ominous shadow indeed.

Susanne Berger is a historical researcher and former consultant to the Swedish-Russian Working Group that investigated Wallenberg’s fate in Russia from 1991-2001.