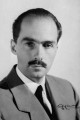

Aristides de Sousa Mendes, at the time of the Nazi invasion of France, when he was still Portuguese consul to Bordeaux, a job he was destined to lose

Aristides de Sousa Mendes, at the time of the Nazi invasion of France, when he was still Portuguese consul to Bordeaux, a job he was destined to loseWith the Nazi invasion of France came an order from Portugal that no Jews or dissidents be granted passage. But one man stood tall against the decree – and in issuing visas for 30,000 people, Aristides de Sousa Mendes was to risk everything. Seventy years on, the people whose lives he saved are battling to restore his honour…

Standing in front of 14 Quai Louis XVIII, I am struck by the beauty of the placid Bordeaux scene. The September sun sinks into the honeyed stone and the topaz sky spreads over the wide waters of the Garonne. Bordelais society parade the esplanade. It is une scène tranquille. Yet it was here, in this distinguished apartment building, during a week in June 1940, that chaos reigned. And it was here that one man performed the greatest act of rescue by an individual during the Second World War. One that even surpasses Oscar Schindler’s bravery. Seventy years on those actions are now having their final repercussion.

Aristides de Sousa Mendes was an unexpected hero. At the time of the German invasion of France he was the Portuguese consul to Bordeaux, a Catholic gentleman of aristocratic origins in late middle age. Born in Cabanas de Viriato in July 1885, he was the twin brother of the foreign minister and had for three decades loyally served Portugal as a diplomat. It was a career that had telegrammed him out to Kenya, San Francisco, Zanzibar and Brazil. After nearly a decade stationed in Antwerp, he was eventually appointed Portuguese Consul to Bordeaux, housed in his second-floor residence on the quay.

In photographs from his early years as an attaché he appears both brooding, with his inquisitive brow, and welcoming, thanks to a measured smile. He looks directly at the lens, as assured and poised as his formal, high-collared diplomatic attire. He and his wife, Maria Angelina, had 14 children. As war broke out Aristides de Sousa Mendes was a man with plenty to lose.

The Nazi advance through France made Bordeaux a powder keg. Its population ballooned as millions fled south in an exodus from Paris and the northern departments. A mad scrum of spies, politicos, governments-on-the-run and refugees jostled for a way out of the country. They huddled, struggled and bartered in the face of dive-bombers and mass hysteria. And Sousa Mendes was expected to provide yet another hurdle. In appeasement to Hitler, the Portuguese dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, issued his “Circular 14”, decreeing that no Jews or dissidents were to be granted passage to Portugal.

To Sousa Mendes the dictate contravened the traditional principles of his country. His friendship with a rabbi added further impetus. He took to his bed in a two-day crisis of conscience after which he rose determined. “I cannot allow all you people to die,” he announced to the consulate staff, who made note of his historic statement. “Many of you are Jews, and our constitution clearly states that neither the religion nor the political beliefs of foreigners can be used as a pretext for refusing to allow them to stay in Portugal. I’ve decided to be faithful to that principle, but I shan’t resign for all that. The only way I can respect my faith as a Christian is to act in accordance with the dictates of my conscience.”

On 17 June a production line was set up, at which he issued 30,000 visas, passports and travel documents. (After two days at the consul, Sousa Mendes continued at the border towns of Bayonne and Hendaye until stopped on 23 June.) Twelve thousand of those helped were Jews. Others who found salvation include the last Crown Prince of Austria, Otto von Habsburg, the Hollywood actor Robert Montgomery and the entire Belgian cabinet. The stateless and the desperate queued around the clock, outside, on the stairs and inside his flat, just to be seen.

On the day Sousa Mendes took his stand a few hundred metres away on the Allées de Munich another man of principle was fighting his own campaign. General Charles de Gaulle was billeted in the Hotel Splendide where the French government had set up base and where a struggle was underway between the pacifiers and the crusaders in the cabinet. That night, as Sousa Mendes sat outside the consulate authorising visa after visa, De Gaulle flew out of the city in an RAF Dragon Rapide to set up the Free French Forces in London. Behind him he left Marshal Philippe Pétain to capitulate and doom France to a humiliating and compromising occupation.

After further defying his government, by assisting at the border, Sousa Mendes was hauled back to Lisbon by a seething and upstaged Salazar who declared him mentally unfit. “Even if I am dismissed,” said Sousa Mendes, “I can only act as a Christian, as my conscience tells me.”

Dismissal was the least of it. He was stripped of his diplomatic status, his pension and his right to practise law, his original profession. No one, the state ordered, was to reach out to him or his family. He was declared “a disgraced non-person”. People crossed the road in his presence during those years of domiciled exile. All but one of his children left the country in order to start anew. Some of his family turned ‘ on him in anger. For 14 years the honourable consul was a pariah, marooned in his family home of Passal in the heartland of Portugal. He died in 1954, six years after Maria Angelina, in abject poverty in a Franciscan monastery.

This June I Googled a gem. Utah’s Salt Lake Tribune reported a daughter’s unusual birthday gift to her father. Olivia Mattis introduced her father Daniel to Ari Mendes. A lifetime ago on a dusty French street eight-year-old Daniel, sheltered from the eye of the storm by his parents, was handed a visa signed by Ari’s grandfather. The family, at that time named Matuzewitz, had the key to a long corridor that took them over the border, through Spain and Portugal to Brazil and finally through the doors of the US.

I contacted Olivia Mattis and learnt of the ripple effect of the drama. “Prior to getting to know the family, I viewed the Sousa Mendes story as my father’s experience, his memory and an event that happened to my family decades before I was born,” Mattis told me. “But coming face-to-face with them has been a shock. Here are people who have suffered terribly: poverty, exile, slander – you name it – just so that my own family and other families like mine could live.” Mattis introduced me to her online network of far-flung members of the Sousa Mendes clan and the families of those saved. This disparate group’s mission is alive on Facebook as they campaign to further honour his deeds.

Many of those helped took up the baton of kindness held up by Sousa Mendes. Lissy Jarvik has forged a career in psychiatry and is now Professor Emerita of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at UCLA School of Medicine. However, in the summer of 1940, she was a frightened 16-year-old girl. “My parents, my 14-year-old sister and I were living in Amsterdam,” she remembers. “We made our way to Paris, tried to leave for England from Calais but ships would take only British passengers, even Dutch ships. Years later we found out that we tried to cross the Channel during the Dunkirk evacuation. We went back to Paris and eventually made our way down to Biarritz. It was the end of the line and we decided that if we could not escape before the Germans conquered France, we would go into the sea and swim out as far as we could in the general direction of England. One day, one of my father’s friends came running with the news that the Portuguese government was giving visas and to bring all the family’s passports and quickly come to Bayonne.”

It was there that Sousa Mendes’ signature allowed their passage. “We were on what turned out to be the last train leaving France with refugees aboard. Our train was sent to Figueira da Foz, where the Portuguese population of the village, who had never seen a Jew, warmly welcomed us. They were totally surprised that we looked like normal human beings,” says Jarvik. Sonja, Jarvik’s sister, summed up the familial importance of the story. “Aristides de Sousa Mendes saved my life. He enabled me to have a family that includes professionals whose lives are very much dedicated to helping humankind. In that way the value of his sacrifices has increased exponentially in succeeding generations.”

During my stay in Bordeaux I visit the ramshackle office of Hellen Kaufmann. She runs the AJPN (L’association Anonymes, Justes et Persécutés durant la Période Nazie). This shoestring charity has created a dizzying database of individuals who assisted those targeted by the Nazis. It is an extraordinary catalogue of human salvage covering every town in the country. She shares the room with Manuel Diaz, président of the Comité Français Aristides de Sousa Mendes. Together they aim to complete a full list of every person saved that summer.

Kaufmann is a petite, black-haired firebrand. Smoking her rolling tobacco and sipping her espresso, she settles into an armchair, knees tucked underneath her. What she tells me puts a more expansive light on the events. Kaufmann believes that Sousa Mendes’ actions were pivotal to the reconstruction of Europe after the war. It’s not just the amount of people he saved but who many of them were. The governments of Belgium and Poland, the royal families of Luxembourg and Austria, along with political activists from throughout the continent. These were to be responsible for rebuilding the framework of Europe when hostilities ended. “We had real people and honest people who escaped in June 1940 and came back after war to start again,” says Kaufmann. What is extraordinary, she points out, is that Sousa Mendes had no knowledge of the holocaust to come but acted on intuition.

In the mid-1980s Otto von Habsburg wrote to Antonio Moncada Sousa Mendes, one of Sousa Mendes’ 39 grandchildren, who is a teacher and sits on the board of the Fundação Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Portugal. “I wanted to say to you in writing how eternally grateful I am to your grandfather,” stated Habsburg. “At a time when many men were cowards, he was a true hero to the West. ” It was a feeling shared by the Great–Duchess Charlotte de Luxembourg who judged that “above all, it is his merit, shown at a time of tragedy and panic, that will forever be remembered by the refugees of Luxembourg”.

In 1966 Sousa Mendes was posthumously made one of the “Righteous Among the Nations”, the honour given by Israel to those who assisted Jews during the war. It was the first step along the long road to rehabilitating his name and honour. It wasn’t until 1988 that the Portuguese parliament officially dismissed all charges, restoring his diplomatic status and promoting him to ambassador. In death he received a standing ovation from the institution that ruined him. Yet, of the many books written in France on the events of 1940, none mentions Sousa Mendes.

Kaufmann believes “The Angel of Bordeaux” wasn’t acting out of character. “He did many crazy things in his life,” she says. During his diplomatic service he used consulate funds to have a giant figure of Christ made for his Belgian office and had an elongated car designed, a family wagon to ferry his expanding number of children. He also accepted paternity for a further daughter by a local French woman. “He was a funny man,” laughs Kaufmann. “He liked the life, the sex, to eat and music and dancing.”

“There are many families out there who do not know he saved them,” she explains. One of these was Harry Oesterreicher, whose grandparents and father were granted a visa. After receiving an email from Kaufmann he attended an anniversary visit to the consul building this June. “He had a crying week,” says Kaufmann.

“One could visualise the refugees waiting in the streets below, sleeping on the stairs,” says Oesterreicher. “I pictured myself walking in the footsteps of my grandfather, Jacques, as I climbed the first two flights, and could almost feel the hope, and also the fear which he must have felt as he himself ascended.”

The current Sousa Mendes diaspora are now looking for a final act of reparation. “The present generation of the Sousa Mendes family, that is, the grandchildren, are in the position of having the chance to compose a happy ending to their family’s epic tragedy,” says Mattis.

Sixty miles south-east of Porto lies the Portuguese village of Cabanas de Viriato. The Serra da Estrela peaks jag along the horizon and the surrounding landscape is ripe with the Dao grape. Among the alleys and streets one building imposes itself: Passal. A century ago it was known as “The Palace” yet for decades the local schoolchildren have called it the “mystery mansion”. ‘

This great 19th-century manor was the Sousa Mendes family home. At its sale, after Aristides’ death, creditors found doors were missing. They had been broken up for firewood in those last years of his half-life. From thereon the estate lay as ruined as Sousa Mendes’ reputation. Today it is a place of loss and the weary, faded potential for restitution. In 2001, the house finally returned to the family through compensation and donated funds from the Portuguese government. From that endowment the foundation was born. Their dream is to turn this ghost of a building into a museum to honour the legacy of Sousa Mendes and to house a human-rights library.

Speaking from his home in Portugal, Antonio, now in his sixties, still recalls his grandfather’s jovial presence in the house. “I was four-and-a-half when he died,” he says. “I just remember a nice figure, this nice character, he liked to laugh and make fun.” Antonio’s allegiance to his country was damaged by its treatment of his grandfather. “I left Portugal. I deserted the army. I was going to be sent to the war in Angola but I left the country and went to Belgium as a political refugee and then I made my life in Canada.” Now he has returned to a country scarred by the Salazar regime.

“The house is now in a big mess,” says Antonio. “The Portuguese government, after a time, decided that it would be a national monument, it has the highest status of the Ministry of Culture. It is protected by that but they don’t give the money.” He laughs at the absurdity of how the foundation has been tied up in red tape for the past few years. The initial works to make the site safe are about to begin. Once this has been achieved, 80 per cent of the development’s cost will be funded by governmental contributions. Antonio and the foundation work with private donors to fill the shortfall.

They are not alone. Lissy Jarvik and Olivia Mattis have set up an American wing (US-Based Sousa Mendes Foundation) in order to draw support from overseas. The museum is set to be the only place in Portugal to commemorate the Second World War and human rights.

While trapped in a post-war state of purgatory, Sousa Mendes failed to succumb either to self-pity or regret. “I could not have acted otherwise,” he declared late in life, “and I therefore accept all that has befallen me with love.” Perhaps it has been harder for his family. Can there now be resolution for them with the opening of Passal as a museum?

“Yes, yes it will. Certainly,” says Antonio. “The story won’t finish because we want to perpetuate the memory of his actions and teach human rights and how sometimes civil servants and people with responsibilities have to follow their conscience. That’s a big lesson. But certainly it will have a sense of closure regarding the punishment and the story of migration.”