Journalist Eyal Press set out to examine what makes people come forward during ‘dark times’ to defy authority in order to prevent evil acts. But not all his moral heroes necessarily belong in the same august group

Beautiful Souls:

Saying No, Breaking Ranks, and Heeding the Voice of Conscience in Dark Times,

by Eyal Press

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 195 pages, $24

Nothing about Paul Gruenin-ger, a police commander in northeastern Switzerland, would have marked him as someone likely to risk his career in order to rescue Jews from the Nazis. The unexceptional son of an unexceptional cigar shop owner, Grueninger was not particularly interested in affairs beyond the little border town of St. Gallen, where he made his home and his living. He certainly had no interest in Jewish or political matters. In fact, he had no compunctions about cooperating with the Gestapo in the late 1930s to hinder the flow of antifascist volunteers traveling through Switzerland on their way to fight Franco during the Spanish Civil War.

Yet just a few years later, he brazenly defied his superiors’ orders to keep German and Austrian Jewish refugees out of Switzerland. Grueninger falsified documents that helped hundreds of Jews find a haven from Hitler. When his activities were discovered, he was fired from the police force and heavily fined. Treated by his countrymen as something akin to a traitor, Grueninger lived out the rest of his life in near-poverty.

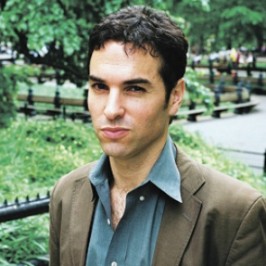

The example of Paul Grueninger is the first of four case studies that are at the heart of “Beautiful Souls,” an examination by Eyal Press, a New York-based journalist and son of ex-Israelis, of the factors that lead some individuals to disobey authority.

Grueninger, who died in 1972, left few clues as to his motives and did not fit easily into any of the various theories put forward by sociologists and philosophers about defying authority, which Press explores at intervals in his narrative. After interviewing Grueninger’s daughter as well as some of the refugees whom he rescued, Press concludes that in Grueninger’s case, it was the emotional impact of meeting the refugees face to face that transformed him from passive bystander to active rescuer.

Most Swiss police captains avoided direct encounters with refugees by delegating the responsibility for dealing with them to subordinates. “Paul Grueninger didn’t,” Press writes. “Every day, refugees showed up at his office, begging to stay in Switzerland. Every week, he witnessed scenes that made it resoundingly clear what enforcing the [anti-refugee] policy would mean.” It was “seeing the fear and desperation in their eyes” that enabled Grueninger “to see the refugees as people,” and moved him to aid them.

Press’ second “beautiful soul” is Aleksander Jevtic, a Serb who knowingly misidentified a number of Croat prisoners as Serbs in order to save them from being tortured or killed by his fellow Serbs in 1991, after a battle during the Yugoslav war. After considering, and discarding, various textbook theories, Press eventually concludes that Jevtic acted primarily as a result of two factors: the fact that he himself was once sheltered by Croats, and a thick-skinned personality that left him unconcerned about fitting in with the people around him in any particular situation.

Slippery slope

So far, so good. Two cases of individuals who were unexpectedly thrust into potentially life-or-death situations and chose good over evil despite the danger to themselves, disobeying an immoral authority in order to do the right thing.

It is at this point that Press begins heading down a slippery slope. Case study No. 3 involves a young man whose defiance is aimed not at perpetrators of genocide or ethnic cleansing, but at the State of Israel, which, whatever its flaws, is a free, democratic and civilized country.

Avner Wishnitzer is one of a small group of young Israelis who, in 2003, announced that they would refuse to serve with their reserve army unit in the territories, because of their opposition to Israel’s policies there. What Wishnitzer is doing in a book with Paul Grueninger and Aleksander Jevtic is not readily apparent. Disobeying orders to hand over Jews to the Nazis or to choose victims of ethnic cleansing is one thing; surely disobeying orders to man checkpoints or frisk potential suicide bombers, no matter how annoying to those being frisked, belongs in another category altogether.

There is nothing automatically admirable about disobeying authority. It matters who is being disobeyed, and why. When the United States entered World War II, a handful of radical Reform rabbis and other Jewish pacifists, calling themselves the Jewish Peace Fellowship, disobeyed their draft orders on the grounds that all war, even war against Adolf Hitler, was immoral. They were not beautiful souls. They were dangerously naive souls who, if they had had their way, would have paved the road to global Nazi conquest.

The question of the consequences that these individuals endured or risked enduring is also relevant. Grueninger was, at the very least, risking his career. Jevtic could have been risking his life. The consequences Wishnitzer faced were of a rather different order. He and his cohorts were expelled from their army reserve unit. There were also some nasty e-mails, and an aggressive television talk show host “impugned his integrity.” Yet Wishnitzer and company also had many political compatriots who rallied around them. Wishnitzer does not seem to have lost any job because of his disobedience. And now he will enjoy a measure of international fame, thanks to a book that elevates him practically to the level of Raoul Wallenberg.

The World War II conscientious objectors, incidentally, likewise seem to have made out reasonably well. Certainly they were not ostracized by the Jewish community. One of their leaders, Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld, later served as president of the American Jewish Congress, the Synagogue Council of America and the Central Conference of American ?(Reform?) Rabbis. Another, Rabbi Abraham Cronbach, served as a faculty member at Reform Judaism’s rabbinical school, Hebrew Union College. There is even a chapel named after him at the Leo Baeck Education Center in Haifa.

Whistle-blower

The fourth “beautiful soul” further dilutes the entire concept of defying evil. In the autumn of 2000, Leyla Wydler, a financial adviser at a Houston-based investment firm, became suspicious that the company was not informing its investors about the risks involved in some of the certificates of deposit it was offering. Wydler’s persistence led to her dismissal. Later it turned out the company was rife with corruption, and Wydler ended up testifying at a hearing of the Senate Banking Committee, where, Press reports, “her speech drew a standing ovation.” Not to belittle whatever difficulties Wydler suffered after losing her job, but it seems to be quite a stretch to argue, as Press does, that the target of her disobedience, the risks involved, and the actual consequences she endured earn her a place alongside the likes of Paul Grueninger and Aleksander Jevtic.

Everyone loves a good David-versus-Goliath story, and that’s how “Beautiful Souls” starts out. But by the end, it reminds us that not every would-be David deserves that title, and not every alleged Goliath deserves it either.

Dr. Rafael Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. His latest book ?(coauthored with Prof. Sonja Schoepf Wentling?), “Herbert Hoover and the Jews: The Origins of the ‘Jewish Vote’ and Bipartisan Support for Israel,” will be published in April.