“Hope and perseverance helped me survive,” says professor Shevah Weiss.

Professor Shevah Weiss was born in Boryslaw, Poland, in 1935, into a Polish-Jewish family. Rescued during the German occupation of Poland, he emigrated to Palestine in 1947. He eventually became a professor of political science at the University of Haifa in 1975. He was Speaker of the Knesset and a long-standing Member of the Israeli Parliament, was Ambassador of the State of Israel to Poland between 2001–2003. A Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, Weiss still lectures at Warsaw University, living in both Warsaw and Haifa. Many see him as Poland’s honorary ambassador in the world. Aleteia’s Iwona Flisikowska spoke to Professor Weiss about his life.

Iwona Flisikowska: Professor, you and your family miraculously survived the Holocaust, or the extermination of the Jewish people prepared by the German invaders. How do you see it today?

Professor Shevah Weiss: The fact that I was saved is truly a miracle. Just as it was a miracle to save any single Jew during this inhuman war. Throughout my life I have been wondering if — since this is a miracle — you must believe in God? And all the time, even now, I have been looking for an answer: “Why did all this genocide ever happen? Why?” I cannot hear the answer, even though so many years have elapsed since.

As a six-year-old child, I needed help. And we were helped by ordinary yet heroic people, our neighbors from Borysław. Let us remember that only in Poland, everyone who was helping the Jews was killed — immediately and without trial. When we escaped from the ghetto, our first hiding place was the home of Ms. Anna Góralowa, a friend of my mother’s, her schoolmate. Anna was a deeply religious Catholic and she simply hid us in a chapel. I sat in this unusual place with my mother and sister: we found shelter in the shadow of the arms of the Crucified, literally.

Ms. Maria Potężna helped us, too; her name, which means “powerful” in Polish, matched ideally her unbreakable character, because she helped us until the end of the war. I remember how Ms. Potężna brought me, a small boy hidden under the bed, a glass of milk. I will remember this simple gesture till the end of my life. The escape and the hiding were just the beginnings of our national Gehenna. It was difficult to live, hoping against hope.

Yet it was this hope that helped you to survive. Still, I cannot imagine living for eight months behind a double wall only 60 cm in width, with several people at that.

I think you would have been able to survive. We have no way of knowing how much we can bear. It’s life itself that is the ultimate litmus test. My father prepared a hiding place for us: between the wall of our store behind the cabinets and the wall of the warehouse he fashioned a room about 60 centimetres wide, where we all hid: my parents, my sister, my brother and I, my mother’s sister, her husband and son. There was also our neighbor Bachman.

Unfortunately, my uncle could not cope with this mentally and left the hiding place, leaving his wife and son. Later I found out that the Germans had killed him.

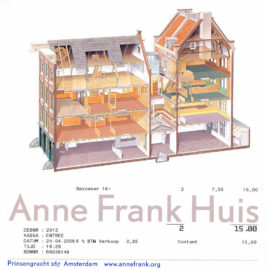

My father had prepared our “wall” well: he built the bunks, one on top of the other, up to the ceiling. We had to lie down all days. Many years later, when I was in the Netherlands, I visited Anne Frank’s house and saw that her father also hid in a double wall. Still, Anne did not survive, and we did.

And then we lived in the basement of a house which was a children’s orphanage. The cold and damp nights were a true nightmare. My father fell ill with tuberculosis under these conditions. We had to stand watch at night so that no one on the outside would hear our Dad’s loud coughing or snoring.

Hygiene was an ordeal. I cannot bring myself to recall it. Our beloved neighbors provided us with food and water. My father cooked a soup consisting of one potato and water for our whole group. But in the end, we were reduced to chewing book covers made of genuine leather.

These books took up a large part of our possessions: I must have read The Count of Monte Cristo 10 times. During the day, when children were playing in the orphanage and caused a great commotion as children do, we could even talk. A bit of light reached our hiding place through a tiny window, or rather a slit, and we could read books.

When we finally dared to get out of our blind basement, we met neighbors on the way. If they could have, they would have cried out. They looked at us as if they saw ghosts.

I can imagine how scared they got: we were totally emaciated, wore rags, had long hair, and my father sported a long beard like a Jewish patriarch. We were all very dirty and had lice. We sat somewhere in the corner, because we no longer had the strength to go on. We were moreover afraid that the front would withdraw, and the Germans would return and kill us.

In the end, we plucked up the courage to go “towards the light.” The day was beautiful and sunny. For the first time in many months I was able to stand on straight legs; in the basement we had moved on all fours as there was so little space. We survived thanks to our neighbours: the families of Góral, Potężny and Ms. Julia Lasota.

Righteous Among the Nations …

Jan Goral holds a Righteous Gentile diploma he received from Israeli Ambassador Shevah Weiss in 2001. AP

Jan Goral holds a Righteous Gentile diploma he received from Israeli Ambassador Shevah Weiss in 2001. APYes, each of these families belongs to them. I had the pleasure and honor to personally participate in the award ceremony of the Righteous Among the Nations for Anna and Michał Góral as well as for Maria and her son Tadeusz Potężny. It all happened in 2001.

When Jan, the Górals’ grandson, accepted the diploma from my hands, he said that his grandparents believed that hiding and helping Jewish families was something obvious, normal and human. We shared life.

Ms. Lasota was honoured by Yad Vashem, too. The largest numbers of the Righteous Among the Nations come from Poland. Most olive trees are planted in Yad Vashem with plaques bearing the names of heroic Poles, such as Irena Sendler, for instance. Your heroism was special, because as I said before, every Pole risked immediate execution for saving the Jews. This was the fate of the Ulma family.

After the war, you left for the newly established State of Israel. Why?

It was indeed a return to our Promised Land, which had been talked about and longed for in my family for generations. I was overjoyed: I was very ambitious and wanted to excel at everything.

Among others, I worked in the radio station, which was then a sign of social prestige. Earlier I worked in a kibbutz and I drove a tractor pretty well. I really thought that any work I would do with my heart would be appropriate so that our hard-won sense of belonging to a specific place and people could develop.

I could just as well be cleaning streets or stack pavement elements; I was really thrilled about the Promised Land. I met my future wife, Esther. She really was a beautiful woman. A girl from a cover of one of our magazines. I wondered if I had any chance. We started going out and after one of my visits to Esther’s family home, her mother said to her quietly: Marry him, because one day he will be a statesman and a great person.

I do not know what prompted her to see “a great man” in my humble person but this is what she said. For almost 50 years we were a truly loving and understanding married couple. Our daughter, Ifat, and son, Noam, are the fruit of our marriage. I also have a granddaughter, Shira.

Esther accompanied me and supported me in my diplomatic work. It is true what they say in Poland (and probably not only here) that a good and wise woman is the root of any man’s success. Esther has not been with me for 12 years now, but I believe she looks at me from heaven and continues to support me.

The Jews of Polish origin had a significant share in the creation of this Promised Land, for example the famous Ben Gurion …

That’s true. David Ben Gurion was born in Płońsk, 60 kilometres off Warsaw. He was one of the founders of the State of Israel, our first prime minister. I do not know if you are aware of it, but there were plans that Polish would be one of the official languages of Israel, apart from Hebrew.

Precisely because many of us were born and brought up in Poland. My parents spoke Yiddish and Polish at our home in Haifa. The parents belonged to all the Polish libraries in Haifa. They were keenly interested in European themes but kept abreast of our Israeli issues. They listened to my radio broadcasts. It was a great experience for them when they heard their son’s announcement: This is Shevah Weiss speaking. They supported me when I was professor and an MP, later the Speaker of the Knesset.

You had the opportunity to meet extraordinary people, the “great men and women of this world.” However, you often talk about your meetings with Pope John Paul II.

I can say that I was lucky in life to have met such an amazing person as John Paul the Great. Yes, he was great in his modesty, spiritual strength, and incredible ability to reach to the heart of every man, regardless of his religion, nationality, or skin color.

He had respect for every religion, or, figuratively speaking, for the way of each and every man. He called us Jews the “Elder Brothers in the faith.” I remember a touching meeting at Yad Vashem, when John Paul came to us in 2000. I will never forget how he held my hands in his.

And when he learned that I was born in Borysław, he said: It’s not that far away from Wadowice, two hundred kilometres, perhaps two hundred and sixty. I replied: I do not know, but the Holy Father is certainly right, because the pope is infallible. Then there was the meeting at the Wailing Wall: John Paul II, his hand trembling, inserted a sheet of paper with a prayer into a crevice of the wall.

Professor, many readers of Aleteia are young people from different countries. What could be your special message to us?

Once again, I will refer to John Paul II and to his words: We are all children of one God … Let us remember it. Every day, let us build this world, everyone in the place which has been entrusted to her or him as a task, and also often as a challenge. Hope and perseverance do wonders. I, a six-year-old child who looked through the slit of a dark basement hoping for a better tomorrow, am an example of this.