The family of Raoul Wallenberg have made one more appeal for the truth about what happened to the Swedish diplomat on the eve of the centenary of his birth.

Wallenberg saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Nazis by issuing them with Swedish papers during 1944-45, only to then disappear in Soviet custody after the war.

After years of official denial, a joint Russo-Swedish working group was set up in 1991 to establish the facts. But it failed to draw any definite conclusion.

“The family wants now to get the truth,” says Cecilia Ahlberg, Wallenberg’s great-niece. “We want all the facts about his whereabouts in the Soviet Union, what happened and when it happened.”

Cecilia is sitting in the living room of her grandmother, Wallenberg’s half-sister Nina Lagergren, aged 91. Mrs Lagergren is equally adamant.

“The Russians must know. There’s no question of them not knowing what happened, and we have not had a truthful answer.”

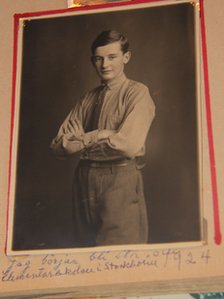

As the summer shadows lengthen on the lawn outside, Mrs Lagergren flicks through a family album and recalls her last Christmas with Raoul Wallenberg.

“He was doing imitations: a Frenchman, an Englishman, a German… and we laughed so much. That was the Christmas of ’43, and one couldn’t imagine that it would be the last time we all saw him together.”

Scarlet Pimpernel

She speaks in the elegant, pre-war tones of the English upper classes – a cut-glass accent and vocabulary honed at a London college in the 1930s.

And it was a British wartime propaganda film, Pimpernel Smith, which gave Mrs Lagergren her first inkling that Raoul would do something special.

The film takes the action of the Scarlet Pimpernel into pre-war Nazi Germany, telling the story of Horatio Smith, a British archaeologist trying to save inmates of concentration camps.

“They couldn’t show it openly in Stockholm, because it was anti-German. So they had a special cinema where we could see it, specially invited, at the British embassy. This was in 1942. And afterwards Raoul said: that is something I would like to do.”

On Mrs Lagergren’s bedroom wall hangs an example of what he actually did: a fading yellow Schutzpass (protective pass), an emergency document that he issued to make Hungarian Jews citizens under Swedish protection.

He would then move them from the ghetto to buildings which he rented and flew the Swedish flag from. Tens of thousands were saved from deportation to Auschwitz.

But as the Red Army approached, he grew increasingly concerned about the dire humanitarian situation in the city – and resolved to make contact with them.

“It was war, and everyone was in danger,” says Mrs Lagergen, “but what one could not foresee was the attitude of the Russians.”

Soviet gulag

On 17 January 1945 he drove off to meet the Soviet forces, but was arrested two days later and taken to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow.

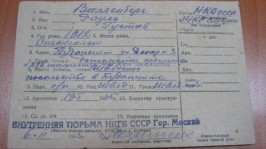

The document of Wallenberg’s arrest was released recently by the Russian authorities to Swedish author Ingrid Carlberg. Intriguingly, Column 13, for the type of crime committed, is left blank.

At the time the Soviets said they had no knowledge of Wallenberg’s fate, although they released other Swedish diplomats separately taken captive.

“My mother went to meet them. She wanted to see with her own eyes that Raoul wasn’t there. That began her martyrdom, one can say, which went on until her death.”

Wallenberg’s mother committed suicide in 1979, refusing to believe Soviet claims – made later – that Wallenberg had died in captivity in 1947.

As late as the 1970s and 80s witnesses emerged saying they had met Wallenberg in the Soviet gulag.

Mrs Lagergren does not like to dwell on the impact all this had on her, though she says she never gave up hope he was still alive.

Cecilia, Wallenberg’s great-niece, describes growing up with the family trauma.

“It was like a veil, it was constantly present – the sadness and the hope when a new witness came up. Then the despair when the witness turned out to be not reliable. I’ve been living with this all my life.”

Prisoner Number 7?

Recent months have seen a new burst of activity. In January, the Swedish foreign ministry began making new inquiries with the Russian authorities.

That followed claims by researchers of new archival evidence, hinging on the existence of a mysterious Prisoner Number 7 interrogated in Lubyanka a week after Wallenberg’s supposed death.

But researchers say the Russians are not giving them full access to the archive – merely to redacted photocopies of some documents. Last month, the family wrote to the Russians demanding they finally provide full and unfettered access.

“They promise researchers access, but when they come to the archive they’re given a photocopy or told a family member needs to be with them. Researchers are not getting the full picture,” says Cecilia.

“A long time has passed and it’s time to get the truth, for the family to finally get peace.”