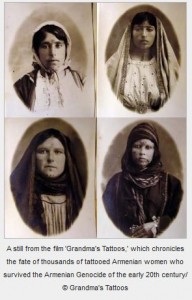

Ever since filmmaker Suzanne Khardalian’s documentary, “Grandma’s Tattoos,” was screened across the U.S. and broadcast on Al Jazeera’s English channel, the response has been overwhelming.

“I’ve been getting hundreds and hundreds of emails and letters,” says Khardalian, who directed and produced the film that chronicles the forgotten story of the fate of women – including that of her own grandmother – who survived the Armenian Genocide.

The letters, some from South Africa, others from India and just about every other country you can think of, relay appreciation and at times shock about the physical, emotional and psychological scars of Armenian women who were distinguishably tattooed, raped and sometimes forced into prostitution at the beginning of the 20th century.

Now living in Sweden and with more than 20 films under her belt, Khardalian spoke to ianyanmag about the sometimes difficult process of talking to genocide survivors, how easily women’s narratives get lost in the vaults of history and how Armenian women today need a big dose of courage.

Q. Why did you decide to make this film?

A. Genocide has been on my agenda for a very long time. What I wanted to do was do something about the genocide in Rwanda, especially tackling the question of gender and genocide – a topic we’ve only begun to start talking about. Usually, the fate of women is not discussed. I met some of these Rwandan women in Stockholm at a conference; these were the women who had been undergoing the horrors of the war and the main problematic issue was of course rape, and rape en masse, in hundreds of thousands, having rape as a strategy you use during genocide to complete it. Of course I was thinking about the Armenian Genocide in the back of mind and suddenly I came to realize that when it comes to the Armenian Genocide or to the Holocaust, there’s so little written about the women.

The amazing thing is when you look at the Armenian case, there’s a huge amount of literature on this and all you read is “and the women were raped,” these very very short sentences…but no details, there’s no story about it. Give me an example. Do you happen to know the name of an Armenian woman who was the hero of the genocide? Fighting that and trying to survive? You don’t have that, and it was very discouraging and I was fascinated by that. Once I stumbled upon those photos, the whole thing took on a very different aspect, the story became very very personal, because suddenly I found out my own grandma was a victim, she was there all the time and we had no idea about it.

I’m not a feminist, but let me say but it is very very strange to see how even in tragedy the destiny of women is somehow by selection taken away or forgotten, or amnesia is organized around it so people will forget.

Q. Often in Armenian history and sometimes literature, Armenian women’s narratives get lost, do you think your film has filled one part of the story, either as a whole or for your family? Do you still have more questions?

A. Oh yes. Look there’s so many questions that very few have been answered. I still feel that my mom is not willing to continue because well look this is something that is associated with shame and feelings of guilt – where in a strange way you are the victim of an atrocity but at the same time you feel you’re responsible for that atrocity. I have been talking to victims of rape, when you talk to these women, very strangely they say the same thing. They’re ashamed, they think they’re responsible for it Everybody thinks that the way to deal with it is just to forget it. If you forget it it will go away, and of course it doesn’t go away.

So there’s lot to discover, the film is only a fraction of what I have been doing. A film is a film, and you have to limit lots of stories. There’s fascinating things to tell, I hope one day I can make a second film on this, there’s a lot to do.

Q. When you went to Yerevan to meet the 104-year-old Genocide survivor – for me that was the most emotional part of the movie, because unlike your great aunt, she was very honest and raw. How did you feel in that setting?

A. I’ve been working with genocide survivors for such a long time now, so I had been working with these old people all the time, they are all very, very sweet and it’s amazing to see how until the end of their lives that these people remember things, especially in their childhoods, there are certain details. I remember one survivor I was filming in France, he had one fantastic segment of a memory. He said, ‘I remember the feeling of my mom’s blouse, that silk feeling on my face when she used to carry me,’ and that feeling, and I could feel it my self, it’s very very small detail, it is about your mom and what ‘mom’ is to you today, and just that feeling on your face about a piece of silk. It’s very abstract and it’s very human.

When I came to Maria Vartanyan in Yerevan, she was sweet – what is fascinating with Maria is that she is so lucid she remembers quite a lot, and one more thing that was different, when I wanted to talk to her, I told her from the beginning, I want you to tell me the story of women, tell me what happened to the women. Do you have any stories like that? And she said, ‘Come back to me the next day.’ She had a whole laundry list of stories, about women she knew and what happened to them and how they survived the genocide. When you look at the interview, it is the first time I’m discussing a subject about sex or slavery with a woman who is 104 years old. I was sitting there and she was telling me for example, how her menstruation stopped and she was praying to god that she would never get pregnant. Details like that. She was telling me that the Armenian men became infertile, they had no sexual potency left. The men too lose their sexual appetite. The men weren’t able to give children as well. She was referring to this when she came to Armenia, especially from Turkey to Soviet Armenia.

Q. What happened when people were reluctant to speak with you about these topics?

A. I remember one case when I was filming in Fresno. I had met this lady, she had a tattooed mother, but she had decided for herself that her mom was not tattooed, people around her, they knew she had been, but she had decided her mom was not tattooed, so it was like talking to a wall, there was no where to go. It as the same with Lucia [Khardalian’s great aunt], you talk and there’s a certain barrier when it all stops. Working with survivors needs a technique, I’ve written a book on this, how to film genocide survivors, it takes time to build trust.

A major problem has been the family of survivors – they’re not willing to bring the issue forward. I didn’t fight against this in this film, it shows it’s symptomatic of the situation we’re in, as a community, as Armenians, it’s a taboo, you don’t want to talk about it, I wanted to show that people are not willing to talk about this. But yet I think we have to talk about it. I’m interested in the process of making this known. I think knowledge is very important in this aspect, knowledge about the fate of the women is very stereotyped when it comes to the Armenian question and changing that is a challenge.

Some said to me ‘Why are u doing this?’ ‘Why are you bringing this into the open, making it public?’ ‘This is considered dirty laundry, this is disgraceful for our nation.’ No I don’t think so, what is wrong in choosing life, because the way I see it, the women who survived, even if they were tattooed, kidnapped, raped and they gave birth to children of the rapists, all this for me is that there were people who chose life. I want us when we talk about these women, I want us to remember them, not as women who were raped, but as the real heroes. Who were the one who gave birth, to all the Armenians living around the world today. We are the children of these women, we just need to accept and be proud of it.

Q. When you made the film and people began to view it, did you have anyone else contact you whose grandma had the same tattoos?

A. Very very many. When I was going around screening this film, after each screening, there were at least 10-15 people approaching me saying ‘my grandma was tattooed.’

Some of these girls never came back to their nation, to Armenian society, they had no chance, they stayed behind because they had no possibility. Today Turkish society has started to talk, about Grandmas that were Armenian. It’s always Grandmas, not Grandfathers, when they’re talking about this…this brings up the issue of identity, what is happening to Turkish identity. I think when we look at this in this way, it becomes urgent matter to look into ourselves and decide what or who makes an Armenian. And because this brings up the issue, do genetics make you an Armenian? if that is the case, look at these raped women who had children, these Muslim Armenians, hidden Armenians in Turkey today , aren’t we supposed to look at them as Armenians? Are Armenians are only supposed to be Christians?

Making this film brings so many more questions, as a collective , for how much longer every time an Armenian has slightly different religion or identity are we going to throw them out, not take them as Armenians?

Q. What are some current issues in the Armenian diaspora, or in Armenia in regards to women that are of interest to you?

A. One, when are we going to learn that women are as intelligent, as talented and as motivated as men are? Not only in Armenia, but in diaspora as well. Look at our organizations, how many women do you see around you? All those committees, they create, how many women are there? I think it’s just stupid, ignorant to ignore the women. We are an essential part of the Armenian nation and if the men decide to discard us, then they’re discarding themselves.

Unfortunately the women are as responsible for this too. There’s a lack of courage, or interest in political issues especially. I want women to be involved in politics, and politics is not just becoming a member of the parliament. If you’re engaged in environment issues, there’s politics as well, everything we do in our lives is politics at the end of the road. I want us to be courageous enough and push the doors open with your elbows.

It’s unfortunate, look we’re living in the States, we’re living in the Europe, but still our women, when it comes to the community you can hardly hear them. If a woman is responsible for a hospital, or a big dept. somewhere or a physicist, if she has the capacity to do that work, we should be able to trust the women with political missions as well.