Kafka was in love with her

MAY 17, 2021, 12:57 AM

Please note that the posts on The Blogs are contributed by third parties. The opinions, facts and any media content in them are presented solely by the authors, and neither The Times of Israel nor its partners assume any responsibility for them. Please contact us in case of abuse. In case of abuse,

Milena Jesenka

Photo: Wikipedia

On the 77 anniversary of her passing, I would like to reflect upon the short life of Milena Jesenká, a singular Holocaust rescuer.

She was born in Prague in 1896. Her mother died when she was only 13 years old and her father, a prominent dentist, was a conservative Catholic believer. Milena was rebellious and she clashed a lot with him. After finishing her secondary school she started studying medicine but she quit after a few semesters.

At the early age of 20, she fell in love with Ernst Pollak, a relatively well-known Jewish literary critic who introduced her to the intellectual circles of Prague. Her father strongly objected to this bond and had her hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital. A few months afterward she managed to get released and married Pollak. Her father was outraged and severed all ties with her.

Milena moved with her husband to Vienna and started working as a fashion correspondent for a Czech magazine. In the Austrian capital, she got to know several literary giants, such as Franz Kafka and Franz Werfel, as well as Max Brod, the former’s biographer and intimate friend. She intellectually thrived there but her marriage was breaking apart.

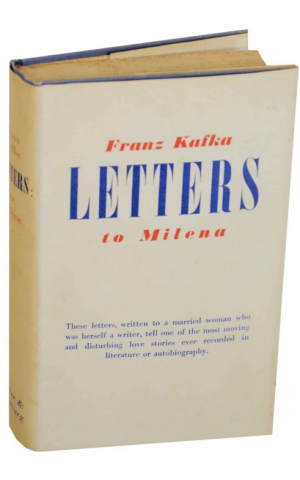

After reading some brief stories by Kafka, Milena contacted the author and asked for his permission to translate them into Czech. This was the beginning of an extensive and passionate exchange of letters that would last till 1923.

Kafka and Jesenká were deeply in love but their relationship was epistolar in nature, except for some brief and sporadic encounters. Eventually, the lovers would accept the fact that their love, intense as it was, had no future.

In 1952, Willy Haas, a renowned screenwriter and literary critic published “Briefe an Milena“, a compilation of Kafka’s letters to his lover, but some fragments were deleted by Haas, who was afraid to embarrass some living people who were mentioned in the letters. Further editions appeared in German and English and the last one in that language contained not only the full and uncensored letters but also some of the ones sent by Milena to Max Brod and her obituary for Kafka.

Argentina’s foremost musical composer, Alberto Ginastera, was so impressed by the book that he composed his Cantata for Soprano and Orchestra, Opus 37 with a libretto based on the actual letters.

Kafka passed away shortly after he had broken up with Milena and following his death, the latter decides to leave her husband.

Back in Praga she starts working as the editor of several influential newspapers and gets acquainted with a number of Czech intellectuals of Jewish and German ascendance.

In 1927, Milena gets married to Jaromir Krejcar, a prominent Bauhaus architect and a year later, their daughter Jana is born.

Milena joins the Communist party and starts writing for its newspaper Svít Práce, but in 1936, heartbroken by the Great Purge in the Soviet Union, she decides to leave the Party.

In autumn 1938, with the annexation of the Sudetenland by the German, Prague gets a massive influx of Jewish refugees. Foreseeing the impending tragedy, Milena started encouraging her Jewish colleagues to cross the border to Poland and flee from there to the West. In the Spring of 1939, following the German invasion, the situation got worse and Milena started to help Czech pilots and Jewish refugees to escape to France using a carefully planned route. Her Kourmska Street apartment became a temporary shelter for many of the fleeing refugees and Milena took care of all their needs, including the supply of forged documents. One of the people she gave shelter to was Eugen Klinger, a Jewish journalist. He tried to convince her to join the refugees and flee herself to the West but she declined his proposal, claiming that “she was in much less danger than the Jewish refugees”.

Eventually, her attitude led her to a tragic destiny. On November 11, 1939, the Gestapo arrested her and after having been in several prisons she was finally deported to the infamous Ravensbrück concentration camp. Due to the deplorable conditions of her internment, her health took a turn for the worse and she died on May 17, 1944, just three weeks before D-Day.

On December 14, 1994, Milena Jesenská was declared as Righteous among the Nations in recognition of her courage.

To me, Milena Jesenká was a remarkable heroine and her legacy will live on forever.