*Author, Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest; Myth, History & Holocaust

Raoul Wallenberg was a heroic Swedish diplomat who made history by assisting and saving thousands of Jews in Budapest during the Holocaust. But Wallenberg was arrested by the Soviet Union and disappeared into the Gulag, never to return home to his family, or his own future.

One of the most admired figures from Holocaust history, Raoul Wallenberg is also one of the most enigmatic. Why did this scion of Sweden’s most important family go to Budapest to save Jews during the Holocaust? And, once there, what did he actually do to save lives?

I have been studying Wallenberg, the man and his mission, for more than 20 years, and this book is the result.

During this time, I came to understand that the more I understood about him, the more interesting he and his place in Holocaust history and memory became.

Born in August 1912 into one of Sweden’s wealthiest families, Raoul Wallenberg is feted around the globe as one of the heroes of the Holocaust.

He has been made an honorary citizen of several nations. Statues, parks, schools, academic institutions, philanthropic organizations and more have been named in his honour.

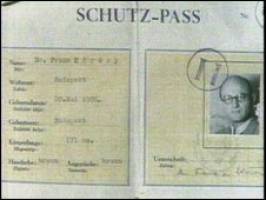

Wallenberg handed out thousands of ‘protective passports’ like this

Wallenberg handed out thousands of ‘protective passports’ like thisAs a young Swedish diplomat serving in Budapest during the Second World War he saved thousands of Jews by providing them with ”protective passports” issued by Sweden’s government.

But, at the war’s end, he was spirited away by the Soviets and died, if their reports are to be believed, on 17 July 1947 somewhere in the cavernous, pitiless surroundings of the KGB’s Lubyanka Prison in central Moscow.

But even this remains a matter for dispute. Did he succumb to a heart attack as the KGB would have us believe, or was he murdered? We shall probably never know.

Indeed, the more I have ”got to know him”, the more acutely poignant his tragic fate in Stalin’s Gulag feels.

Wallenberg chose to go to Budapest to help Jews during the Holocaust, but he didn’t go there believing that he would never see his beloved mother again, nor that he would not be free to pursue his own life after helping so many others retain theirs.

The book I have written, Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest; Myth, History & Holocaust was motivated by my fascination with, and curiosity about, the individual who evolved into one of the most famous names to emerge from the profound catastrophe which was the Holocaust.

When in the early 1990s I began interviewing survivors from Budapest who were either directly or indirectly saved by him, I quickly understood the moral power his work and symbolism exercised on the imagination of so many – and by no means only survivors.

The more I studied what he and other Swedish diplomats in Budapest did (and what their colleagues did earlier elsewhere in Europe), the more I understood why his memory has captured a quite unique space in Holocaust commemoration.

Broken promise

All of this was interesting, yet as a trained Holocaust historian, I was dissatisfied with existing explanations about Wallenberg.

I felt they were superficial, un-contextualized, and unconvincing. The existing publications did not describe his deeds in an accurate historical context, and they, perhaps most problematically for a historian, inflated his actual achievements.

Crucially for my work, I discovered that most peoples’ understanding of Wallenberg was based far more on myth than on sustainable scholarship.

This study corrects the common misunderstandings of Wallenberg’s place in Holocaust history, making it both more real and, I should like to argue, more interesting.

This task could only be done by digging in Swedish government archives. Crucial to understanding Wallenberg’s decision to go the Budapest was to understand his upbringing.

His often moving correspondence with his paternal grandfather, Gustaf Oscar Wallenberg, penned while Wallenberg was a teenager and young man, is closely analysed.

What it shows is a highly intelligent, worldly, and charismatic young man who grasped the ”offer” history made to him in mid-1944 in a quite dramatic fashion.

The Soviets said Wallenberg died in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison in 1947

The Soviets said Wallenberg died in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison in 1947Yet, some of my findings will surprise and perhaps even discomfort readers. The available documentation reveals that certain of Wallenberg’s activities in Budapest were less than noble.

These findings conflict with what most believe they know about Wallenberg. He violated his promise not to do business while in Budapest. Oddly, his Hungarian-Jewish business partner, Koloman Lauer, put considerable pressure on him to look for profit – in the midst of a genocide.

Contrary to popular belief, Wallenberg did not go to Budapest to ”save Hungarian Jewry”. This was impossible, because the majority had already been murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau by the time he arrived.

There is reason to believe that he undertook his mission as much as an opportunity to transform his own languishing reputation as to engage in a ad-hoc humanitarian effort.

That said, when circumstances dictated that he could not return home, his enormous energy and imagination set to saving as many lives as possible.

Raoul Wallenberg did not personally save 100,000 Jews – this idea and figure is part of the web of myth surrounding him. But he, along with his diplomatic colleagues, did help tens of thousands of Jews survive the Holocaust.

I am convinced that what he did requires no novelistic embellishment.

Yet, in a tragedy of classic dimensions, the young Swede who saved the life of so many was unable to live a life of his own.

The saga of his arrest and detention by the Soviet Red Army in January 1945, for reasons still unknown, ended with his never returning to his home and family.

This unredeemable tragedy haunts us still. Nonetheless, it is vital that we remember Raoul Wallenberg not for how he died, but rather, how he lived.

Dr Levine is Senior Lecturer at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest; Myth, History & Holocaust is published by Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd