NEW YORK — It took Ina Polak 35 years to discover the dusty piece of paper that probably saved her and her family in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

It wasn’t until she was cleaning her mother’s New York City apartment following her death in 1980 that she discovered the document listing her, her sister and parents. It was a Salvadoran citizenship certificate.

”My first reaction was ‘Oh, now I understand!’” said Polak, who is 87.

She and her family were Dutch Jews, with nothing to connect them with the distant Central American country of El Salvador. Yet the certificate dated 1944 became their lifeline, thanks to a man named George Mantello.

Mantello, a Jew born in what is now Romania, was one of a handful of diplomats who during World War II saved thousands of Jews and others on the run from the Nazis by giving them visas or citizenships, often without their governments’ knowledge.

They were men such as Hiram Bingham IV, a U.S. consular official in Marseille, France who issued visas and other travel documents that are credited with helping to rescue about 2,000 people; or Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese envoy in Lithuania, thought to have saved 3,500; or Dr. Feng Shan Ho, the Chinese consul in Vienna whose visas got 18,000 Jews to safety in Shanghai.

Best known of all is Raoul Wallenberg of Sweden, whose efforts probably contributed to saving 90,000 Jewish lives in Hungary before he vanished in what became an abiding mystery of the Holocaust.

Now the work of Mantello is getting fresh attention as scholars dig into newly released files and piece together the lives he saved by gaming the diplomatic bureaucracy.

Working as first secretary in the Salvadoran consulate in Geneva, Switzerland, Mantello used a network of contacts to issue papers to Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe between 1942 and 1944 _up to 10,000 documents, according to his son, Enrico Mantello.

The same figure is given by historian David Kranzler, who published a book about the diplomat in 2000 called ”The Man who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz” that also describes Mantello’s critical role in publicizing the so-called Auschwitz Protocol, a description of the Nazis’ biggest death camp by two escaped inmates.

It is not known how many lives were saved by Mantello’s documents — ”definitively, hundreds,” says Mordecai Paldiel, a Holocaust studies professor at Yeshiva University in New York. A letter from Carl Lutz, a Swiss diplomat who worked with Mantello, speaks of ”thousands” saved.

Without the Salvadoran certificate, Polak and her family would likely have been worked to death in Bergen-Belsen or sent to other camps or the salt mines. Instead they were moved to a small camp enclosure full of Jews with Latin American documents, and finally put on a train out of Bergen-Belsen along with 2,400 people and were rescued by US troops in April 1945.

”Back then,” Polak said, if a German official ”saw a paper, and if it had the right stamp on it and the signature, then it was legal. People with these papers were eligible, in the Germans’ eyes, to be sent to a neutral country, to a better camp.”

Mantello sent out notarized copies of the certificates and kept the originals, more than 1,000 of which were found in a suitcase in a Geneva basement in 2005 and donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., by his son three years later.

Now museum researchers are trying to trace recipients of the certificates to get an idea of how many of them actually saved lives and learn the full scope of Mantello’s rescue efforts. The citizenship certificates can be viewed on the museum Web site, http://bit.ly/at7GjV .

Judith Cohen, director of photo archives, says she has discovered how two Dutch families were released from Bergen-Belsen in January 1945 thanks to the documents, sent first to Switzerland and then to North Africa to be exchanged for German prisoners.

”We know that Salvadoran certificates actually helped pull someone out of the concentration camp and send them to freedom,” said Cohen. While calling it ”a very small footnote to history,” she notes the Jewish saying that ”he who saves just one person is like he who has saved the whole world.”

In a speech last year, Cohen noted that ”even when the rescue attempts were unsuccessful, the mere existence of the certificates proves that people cared for others and tried to extend help to friends under occupation to a greater extent than is commonly acknowledged.”

And the areas targeted by the rescuers helps fill in another blank in Holocaust history by indicating ”who knew what when” about what was going on under the Nazi thumb, she said.

After the war, Polak married a fellow survivor, Jaap Polak. She believes that maybe friends of her father gave Mantello the name of her family.

Her father, Abraham Soep, was a diamond manufacturer in Amsterdam, and probably received the citizenship certificate while the family were in a Dutch transit Nazi camp before being sent to Bergen-Belsen (the same camp where another girl from Holland, the diarist Anne Frank, perished).

Citizenship papers entitled their holders to sometimes wear their own clothes instead of prison uniforms and to live in a separate section of Bergen-Belsen.

The difference was critical, said Paul Shapiro, director of the Washington museum’s Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies. ”Remember that if you were in the wrong part of the camp, you were dead.”

While Wallenberg’s activities were initiated and supported by his government, other diplomats acted against their countries’ immigration policies or interpreted them ”very, very, liberally,” says Yeshiva University’s Paldiel, who wrote a book titled ”Diplomat Heroes of the Holocaust.”

In her speech, Cohen said diplomats from Portugal and Romania, as well as representatives of the Vatican and the International Red Cross, helped spread Mantello’s documents.

Those who made a sustained effort to save Jews numbered just ”a few dozen” out of thousands of diplomats stationed in Europe, says Dr. Rafael Medoff, director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Washington, D.C.

As a Jew, Mantello might himself have easily fallen victim to the Nazis. He had held honorary diplomatic positions for the El Salvador government starting in 1939, and had changed his name from Mandel to the more Spanish-sounding Mantello. But he was arrested by the Germans in Belgrade in 1942. He managed to escape to Geneva where he became first secretary of the Salvadoran consulate, and set about saving fellow Jews.

Col. Jose Arturo Castellanos, the consul general, allowed him to issue the certificates, and only later did his government find out about it. El Salvador wasn’t a neutral country at the time — it was backing the Allies, so Mantello had to use emissaries to distribute the certificates.

According to the Washington museum, copies of the certificates produced by Mantello and his team of Swiss volunteer clerks were sent to almost every country in occupied Europe — and even into Auschwitz — with varying degrees of success.

The Germans, for their part, had a use for Jewish prisoners with such documents — to trade for German nationals held in Latin America or the U.S., said Medoff.

”So even when the Germans suspected these documents might not be authentic, they often did not care because they considered these prisoners to be very useful,” he said.

In January 1945, 800 Germans who had been held in the Americas were exchanged for 800 American and Latin American citizens in Germany, and among them were 149 Jews from Bergen-Belsen with Latin American documents, said Medoff.

Robert Fisch, a Minneapolis pediatrician, remembers seeing a citizenship certificate in his house in Budapest in 1944.

”My mother told me, even wrote, ‘don’t give out this paper. It is very important,’” said Fisch, now 84.

While his work on citizenship papers stayed discreet, his role in publicizing the Auschwitz Protocol led to Swiss public protests, prayers and angry headlines. The worldwide protests they stirred may have played a part in the Hungarian government’s decision to temporarily suspend deportations of Jews to Auschwitz.

According to Paldiel, Mantello is insufficiently appreciated because he was an outsider of the Jewish organizations, a businessman who created his own network of volunteers and emissaries. After the war he had difficulty continuing his diplomatic career, and was accused of being financially corrupt, but charges were dropped after an investigation.

One man who appreciated his efforts — and said so in writing — was Lutz, the Swiss diplomat in Budapest who delivered many of Mantello’s documents to Jews.

”You can be assured that … you rendered a valuable service which will get you the thanks _as soon as normal conditions again prevail in this world — of thousands of human beings whose lives you saved,” he wrote in a letter stored at the Washington museum.

Enrico Mantello, now 80 and living in Geneva and Rome, said he remembers his father issuing one certificate after the other.

”He was a very driving, energetic person. He needed very little sleep,” he said. ”He was passionate, he did not take no for an answer.”

But after the war and until his death in 1992, Mantello was a haunted man.

Among those to whom he sent citizenship papers were his parents in what then was Hungary, but they arrived one or two days too late, and his mother and father, along with the rest of the Jews in their town, were sent to Auschwitz and murdered.

”It is a horrible, sad irony,” said Cohen, the museum researcher. ”The certificates were saving people all over Europe, and despite his efforts he was unable to save his own parents.”

Other diplomats who saved lives

Some of the diplomats who, like George Mantello in Geneva, played a role in helping Jewish and other refugees to flee the Nazis:

Hiram Bingham IV: U.S. consular official in Marseille, France, who defied State Department regulations by issuing visas, safe passes and letters of transit to Jews and other refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. Credited with helping to rescue about 2,000 people, including the artist Marc Chagall and author Leon Feuchtwanger between 1940 and 1941. Passed over for promotion after World War II, he was posthumously honored on a U.S. postage stamp.

Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz: German naval attache in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1943, he secretly alerted the Danish resistance that the Nazis were planning to deport Danish Jews. More than 6,000 Jews — more than 90 percent of the total in Denmark — were transported overnight by sea to neutral Sweden. Among them was pianist-comedian Victor Borge.

Chiune Sugihara: Japanese diplomat in Lithuania, issued about 3,500 transit visas to Jews to get them out of Europe as the Nazi invasion loomed. Upon his return home he was fired from the Japanese Foreign Service.

Dr. Feng Shan Ho: Chinese consul in Vienna, defied direct orders and issued many visas to Jews who then escaped the Nazi occupation of Austria. His visas got many Jews out of concentration camps. His government reprimanded him and removed him from his post in May 1940. An estimated 18,000 Jews got to China, many of them with visas issued by Fend Snan Ho.

Giorgio Perlasca: Posing as Spain’s representative in Hungary after the ambassador was ordered out, he established ”safe houses” for Jews and issued protective passes to some 3,000 of them, putting his life at risk.

Carl Lutz: Swiss diplomat in Budapest, 1942-1945, credited with saving thousands of Jews by setting up dozens of safe houses and issuing thousands of letters of safe passage. He helped distribute certificates of Salvadoran citizenship signed by George Mantello at the Salvadoran consulate in Geneva. After the war he was formally chided by his bosses for allegedly overstepping his authority.

Raoul Wallenberg: Swedish diplomat, directly rescued 20,000 Jews from the Holocaust by distributing false Swedish passports or sheltering them on diplomatic territory. He also intervened to prevent the annihilation of the 70,000 people in Budapest’s Jewish ghetto. When the Soviet Army entered Budapest he was arrested and never seen again. Moscow later said he died in prison in July 1947 but many suspected he lived in captivity for many more years.

Sources: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust memorial authority; ”Diplomat Heroes of the Holocaust”, by Mordecai Paldiel; AP research; David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

Pictures

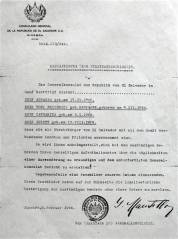

Picture 1: This Jan. 8, 2010 photo shows a copy of the Salvadoran citizenship certificate of the family of Ina Polak, whose maiden name was Catharina Soep, in Eastchester, N.Y. It took 35 years for Polak to discover that the Salvadoran citizenship certificate probably saved her from one of Nazi Germany’s concentration camps. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

Picture 2: This Dec. 29, 2009 photo shows Enrico Mantello during an interview with The Associated Press in New York. Mantello’s father, George Mantello, a Jew born in Romania, was one of a handful of diplomats who during World War II saved thousands of Jews by giving them visas or citizenships, often without their governments’ knowledge. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

Picture 3: This Dec. 7, 1944 photo released by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum shows the Satmar rebbe, third from left, with George Mantello, second from left, in white coat, arguing for the entry of the rebbe into Switzerland with Swiss border guards. Mantello, a Jew born in Romania, was one of a handful of diplomats who during World War II saved thousands of Jews by giving them visas or citizenships, often without their governments’ knowledge. (AP Photo/USHMM)

Picture 4: This April 13, 1945 photo released by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum shows a train stopped in Farsleben, Germany while transporting about 2,500 inmates, primarily Jewish, from Bergen-Belsen to another Nazi concentration camp at Theresienstadt. After a six-day journey they were liberated by the 30th Infantry Division of the U.S. Ninth Army. Among the passengers were Ina Polak and her family, probably saved from death in Bergen-Belsen because they had Salvadoran citizenship papers supplied to them by George Mantello, a Geneva-based diplomat who made it his mission to rescue Jews from the Holocaust. (AP Photo/National Archives and Records Administration)

Picture 5: This Jan. 8, 2010 photo shows Ina Polak speaking during an interview The Associated Press in Eastchester, N.Y. It took 35 years for Polak to discover that a dusty Salvadoran citizenship certificate probably saved her from one of Nazi Germany’s concentration camps. She and her family were Dutch, with nothing to connect them with the distant Central American country of El Salvador. Yet the certificate dated 1944 became their lifeline, thanks to a man named George Mantello. Mantello, a Jew born in Romania, was one of a handful of diplomats who during World War II saved thousands by giving them visas or citizenships, often without their governments’ knowledge. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)