BAD AROLSEN, Germany, Aug. 2 — Like other Holocaust victims, Noemi Ban has gone back numerous times to survey the ghostly field of chimneys at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi concentration camp in Poland where she and her family arrived in July 1944, and she alone survived.

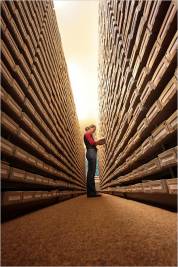

But last May, Mrs. Ban got an even more jolting glimpse into her past, when she visited the Holocaust archive in this tranquil town in central Germany. There, filed in the labyrinthine shelves of records, was a faded scrap of paper that she remembers signing on the day she arrived at the camp from Hungary.

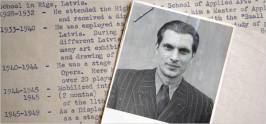

The International Tracing Service contains the files of 51 concentration camps and prisons, and of displaced persons from the 1940s, like those of a Latvian set designer.

The International Tracing Service contains the files of 51 concentration camps and prisons, and of displaced persons from the 1940s, like those of a Latvian set designer.”I was shocked to see my handwriting,” Mrs. Ban, 84, said by telephone from her home in Bellingham, Wash. ”When I signed it, I had no idea why. Why they needed such precise data in that horrible place is amazing.”

The Nazis, of course, kept meticulous records of their mass extermination during World War II, and much of it ended up here, in a closely guarded archive maintained by the International Tracing Service, which is administered by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Now, after more than six decades, the tracing service is opening its vast repository of information — not just to survivors like Mrs. Ban, who have long had the right to see material here, but to scholars who are eager to plumb its depths for fresh insights into an unfathomable horror.

On Aug. 20, the archive plans to transfer digital copies of the first major trove of documents to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and to the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem.

The files cover 51 concentration camps and prisons, and include transportation lists, medical reports, entry documents — like the one signed by Mrs. Ban — and Gestapo prison records. Some 10 million documents in all, they will represent a third of the entire collection at Bad Arolsen.

Prying open the doors of Bad Arolsen has been a lengthy, politically fraught process, and it is not completely finished. Three of the 11 countries that oversee the institution have not yet ratified an amended treaty that would give historians unfettered access to the archive.

In May, though, the 11 countries, among them Germany and the United States, agreed to begin the electronic transfer even before the last three countries — Italy, France, and Greece — ratify the treaty.

”We have interpreted the decision in a way that there is no turning back,” Reto Meister, the director of the tracing service, said. ”It became very evident that the I.T.S. had to change because the victims wanted it to change.”

A tall, rangy Swiss national who has spent his career in places like Iraq and Lebanon for the Red Cross, Mr. Meister has made it his mission to dispel Bad Arolsen’s reputation as a secret Nazi archive — a characterization he contends was always a bit exaggerated.

Outside experts on the Holocaust, who have long pushed for more access, said he had been remarkably successful.

”I have a good deal of admiration for how far he’s moved the place,” said Paul Shapiro, the director of advanced Holocaust studies at the museum in Washington. ”He’s dealing with a staff that, for a very long time, operated in a closed and secretive manner. He also has to balance multiple forces.”

Among those is the German government, which pays nearly $20 million a year for the upkeep of the tracing service and its 320 employees. Until last year, Germany opposed granting wider access to the archive, contending that it would violate privacy standards.

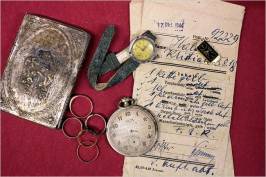

The documents include confidential personal information, like reports of medical experiments carried out on prisoners, and accusations of murder and homosexuality made by the Nazis to discredit people.

Much of the material was discovered by Allied forces when they liberated the camps at the end of World War II. They dumped the files in a complex of vacated SS barracks in Bad Arolsen, which was conveniently located near the border dividing the American and British occupation zones.

Few historians doubt there are a wealth of dramatic, wrenching personal stories in the archives. Mr. Shapiro said he expected enormous interest from researchers, who previously had to rely on documents in government archives in Washington, London and Moscow, which focused less on individual victims than on the functioning of the Nazi system.

Among the files on displaced persons here is a sheaf of drawings and illustrations by a Latvian refugee who was conscripted into the German Army in 1944 and ordered to dig trenches in Germany.

A set designer by training, the young man presented his work — whimsical scenes of thatched cottages and royal palaces — as evidence of his suitability to be granted residency in Argentina. Records from refugee organizations indicate that he may have gone to the United States.

Still, skeptics question whether the material will alter fundamental conceptions about the Holocaust. ”Some people say there will be sensational discoveries, but I am doubtful,” said Wolfgang Wippermann, a professor of history at the Free University of Berlin who studies the Nazi period.

Among those watching Bad Arolsen most closely are lawyers for Holocaust victims and their relatives. They cited the archive this year in opposing a settlement with an Italian insurer, Assicurazioni Generali, over unpaid claims on life insurance policies.

As part of the settlement in February, Generali agreed to give heirs of Holocaust victims until next August to uncover evidence of unpaid claims at Bad Arolsen. Officials there said no one had made inquiries.

Part of the problem for anyone seeking to ferret out information is the archive’s organization, which was intended to help survivors and their relatives trace loved ones, not to serve as a historical record. While there is a vast central database of names, about half the material is not indexed.

”It’s not like using, say, Google,” said Udo Jost, who has helped manage the archive for 24 years and may know its contents better than anyone else.

Adding to the complexity, common names often have many different spellings. (The archive contains 849 variations on the name Abramovitsch, for example.) People’s names were often spelled differently by the authorities as they were moved from camp to camp.

The complexity of the archive, combined with the flood of inquiries, resulted in a huge backlog of requests — 450,000 at its peak earlier in the decade, causing a wait of several years for a response. The backlog is now down to 75,000, but officials say new requests are answered within eight weeks.

As records are transmitted to Washington and Jerusalem, part of this research burden will shift to the Holocaust Museum and Yad Vashem. Mr. Shapiro said he expected a wave of inquiries. Some survivors have already complained that the museum is playing a gatekeeper role.

While it would have been nice to wait for new technology to organize the archive, Mr. Shapiro said, the advancing age of Holocaust survivors — many are over 80 — makes it vital to answer requests as soon as possible. ”That’s a big job, but it’s one we’re committed to doing,” he said.