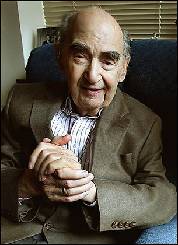

Larry Orbach, a Holocaust survivor, speaks in the living room of his apartment in New York, April 25, 2007

Larry Orbach, a Holocaust survivor, speaks in the living room of his apartment in New York, April 25, 2007BERLIN — Barbara Preusch vividly remembers the day the Nazis searched her Berlin home for hidden Jews _ and left without finding the mother and daughter her family was sheltering.

Now 76 and still living in the same house, hidden behind tall hedges in a leafy suburb, she leads a visitor to the claustrophobic, hidden space between the hallway and a bedroom where Rachela and Jenny Schipper stayed from 1943 to 1945.

”The Nazis were suspicious of us but never found our hideout,” said Preusch, a woman with a stern air, glasses and gray hair. ”They only took our apples and cigarettes.”

Sixty-two years after the end of World War II on May 8, 1945, people like Preusch _ a teenager when her grandmother began helping fugitive Jews _ are being honored with a museum in Berlin.

Israel recognized gentiles who helped Jews escape the Holocaust as early as 1963, and honored 443 Germans at the Yad Vashem Memorial as ”Righteous among the Nations.” But similar honors have been long delayed at home.

The ”Silent Heroes” museum is to open in 2008 in an old tenement building in the center of Berlin. It will be based in Otto Weidt’s former workshop for the blind, where several Jews survived in a secret room, and include two more floors that are vacant and still under renovation.

The new museum will focus on both rescuers and survivors with multimedia presentations and witnesses’ documents that reveal the motivations and dangers faced by the protectors.

About 1,700 Jews survived in Berlin, and an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 non-Jewish Germans actively hid them, according to historian Johannes Tuchel, the head of the German Resistance Memorial Center which is in charge of the museum.

The motivations of the rescuers were manifold, Tuchel said. ”We can’t come up with a typical profile: Some were workers, some academics or devoted Christians; others helped spontaneously or for political reasons.”

There are no exact statistics for the numbers of hidden Jews and their German helpers for all of Germany, Tuchel said. More than 350,000 German Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

”The number of Berlin rescuers might sound impressive at first,” Tuchel said. ”But compared to the 4 million who lived in Berlin at the time and didn’t help, 20,000 are not a lot at all.”

To recognize the rescuers would have come close to acknowledging that there was an alternative to blindly following the Nazis, Tuchel said _ something many Germans in the postwar years were reluctant to acknowledge.

Today’s generation, untainted by their parents’ and grandparents’ crimes, are in some ways more openly dealing with the country’s past and acknowledging different individuals and groups who actively resisted the Nazis.

The Schipper’s ordeal in hiding began after February 27, 1943, when the Nazis started to deport the remaining Jews in Berlin to concentration camps. Hiding was the only chance.

For Barbara Preusch, the Schippers became like family, hiding with them on and off from February 1943 until the end of the World War II in May 1945.

”We shared everything with them: our beds, our food stamps, our joy and our fears,” said Preusch.

”One of our neighbors was an ardent Nazi and he’d constantly watch our home with his binoculars,” Preusch said. ”But he never saw Rachela and Jenny because we had our curtains drawn day and night.”

Preusch, whose grandfather was Jewish and deported to Auschwitz a few months before her non-Jewish grandmother started helping other Jews, said that even after the war it took her a long time until she felt she could trust anybody in Germany.

”Even though I was young, I knew that I couldn’t tell anybody about it,” Preusch said. ”This is the first time I have ever told my story to the public.” However reluctant she is in sharing her story with outsiders, Preusch often talks about the past by phone with Jenny Schipper, who emigrated to the U.S. after the war and now lives in Skokie, Ill.

Weidt’s workshop was turned into a small memorial center by a group of university students a few years ago. In the former workshop visitors can see a secret hiding room that was connected to the small factory and learn about Weidt and his Jewish workers, who produced brooms and brushes. Weidt helped his workers with forged papers, brought them food and even tried to get one of them liberated from a concentration camp after she had been deported.

Weidt hired mostly blind and deaf Jews assigned to him from the Jewish Home for the Blind. But not all of Weidt’s employees were handicapped _ some, like Inge Deutschkron, also worked in his workshop as secretaries. The 82-year-old often gives tours of the workshop, telling visitors about her non-Jewish German rescuers.

”Until a few years ago, nobody wanted to know anything about the ‘good Germans’ who helped Jews during the Holocaust,” Deutschkron said. During the time she spent hiding from 1943-1945, she had about 20 different rescuers who fed, hid and helped her with false identity papers.

Getting caught could mean execution or deportation to a concentration camp, but that did not stop Sylvia Ebel and her family from hiding several Jews at home. Ebel, an 80-year-old retiree who lives in the former East-Berlin neighborhood of Hellersdorf, despised the Nazis, especially after her father, a fervent communist, was imprisoned and later murdered at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

”We sometimes had a whole group of Jews at our apartment, even though we only had two rooms,” Ebel said. They moved frequently to avoid raising suspicions among neighbors.

One of the Jews who temporarily hid at Ebel’s place was Larry Orbach.

The 82-year-old, who emigrated to the U.S. after the war in 1946, remembers how he and Ebel ventured out during Allied bombing to loot food stores.

”You really had guts to go out at night. I was not Anne Frank, hiding in a house. I had to breathe. I had to eat. I had nothing to eat. I couldn’t buy water,” Orbach said during an interview at his home in New York.

Orbach, who worked in the jewelry business in New York and is retired now, is still in touch with Ebel.

”My mother always said, they are part of the family,” Ebel said. ”It wasn’t a question of receiving awards or feeling heroic _ they simply had to live and survive.”