Ingrid Carlberg’s richly detailed ‘Raoul Wallenberg: The Biography’ presents fresh facts about the Swede who saved so many Jews, but is unable to answer the gnawing question surrounding his fate in Soviet custody.

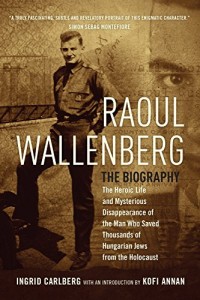

“Raoul Wallenberg: The Biography,” by Ingrid Carlberg, MacLehose Press, 640 pp., $29.99

Two great mysteries surround the life of famed Holocaust figure Raoul Wallenberg: Why was he willing to risk his life to save Jews from the Nazis? And what exactly happened to him after the Soviets took him into custody in 1945?

In this richly detailed biography, Ingrid Carlberg, a prominent Swedish journalist, describes a number of instances in which the young Wallenberg, who was born in 1912 in Sweden, interacted with Jews prior to the onset of the Holocaust. There was the Hungarian Jewish classmate in grade school whom he protected from anti-Semitic bullies. There were the months he spent vacationing in Haifa in 1936-37, where he “heard horror stories about the situation in Germany” from Jews who had fled from the Nazis. There was Wallenberg’s intercession, in Berlin, on behalf of a German Jewish business associate who was arrested during the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom. There was even the belated discovery by Wallenberg, who studied architecture in the United States but ended up working on behalf of his family’s business, that one of his grandmothers had a Jewish grandfather.

Still, to what extent any of these experiences influenced Wallenberg’s later actions is unclear.

One might imagine that the dramatic smuggling of more than 7,000 Danish Jews to Sweden in 1943 inspired Wallenberg. The Swedish government, which until that point had shown relatively little interest in the plight of the Jews, extended itself far beyond what other neutral European nations had been willing to do. Yet Carlberg gives no indication that the Danish episode had any impact on Wallenberg, and given the extraordinary amount of detail in this book, one must assume that if Wallenberg had written or said anything about the Danish rescue, she would have reported it.

By the spring of 1944, only one major European Jewish community still eluded Hitler: the approximately 800,000 Jews of Hungary. Even before then, following an autumn 1943 visit to Budapest, Wallenberg described to his Jewish colleagues “several worrying ant-Semitic incidents” that he witnessed. Wallenberg visited Budapest periodically in connection with his family’s food import-export firm, the Mid-European Trading Company, and over the years, Carlberg notes, he “acquired an impressive skill in bureaucratic gambling, that he would have so much use of later, in his rescue work.

On March 19, 1944, the Germans occupied Hungary. Hundreds of thousands of Jews residing outside the major cities were forced into makeshift ghettoes where starvation and disease were rampant. Soon, under the direct supervision of Adolf Eichmann, deportations to Auschwitz began — in full view of the world. “Jews in Hungary Fear Annihilation,” read the headline of a report in The New York Times, five days before the deportations began, warning that the Germans were “about to start the extermination” of Hungary’s Jews, who would be killed by “gas chamber baths” and other methods.

Three days after the deportations began, a Times article headlined “Savage Blows Hit Jews in Hungary” began: “The first act in a program of mass extermination of Jews in Hungary is over, and 80,000 Jews of the Carpathian provinces have already disappeared. They have been sent to murder camps in Poland.”

Similar reports appeared in the Swedish press, and there is no doubt Wallenberg followed the news, but it took a series of remarkable political developments in Washington to set the stage for his rescue mission.

‘Inexperienced in foreign affairs’

Challenging the Roosevelt administration’s abandonment of European Jewry, Jewish activists known as the Bergson Group in late 1943 sponsored newspaper ads, organized a protest march to the White House and mobilized congressmen to introduce a resolution urging U.S. intervention. (Surprisingly, Carlberg omits this crucial part of the story.) Meanwhile, aides to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. discovered that the State Department had been suppressing news of the mass killing and sabotaging opportunities for rescue. Morgenthau pleaded with the president to act before “the boiling pot on [Capitol] Hill” exploded and Congress embarrassed him on the issue. FDR responded by establishing the War Refugee Board.

Seeking an emissary to go to Nazi-occupied Budapest, the War Refugee Board’s representative in Sweden, Iver Olsen, contacted Swedish Jews with Hungarian business connections. That is how he was introduced to Wallenberg, whom Olsen enlisted to go to Hungary; indeed, the board financed his mission there.

Under Olsen’s pressure, the Swedish foreign ministry agreed to grant diplomatic status to Wallenberg, even though he was really “a grocery salesman completely inexperienced in foreign affairs.” Without that diplomatic appointment, Wallenberg’s rescue work would have been impossible.

By the time Wallenberg reached Budapest, in early July, Hungarian leader Miklos Horthy had halted his government’s involvement in the deportations. (Hungarian officials mistakenly believed Allied bombing raids on Hungarian railroad yards were undertaken in response to appeals by European Jewish rescue activists to bomb the railways leading to Auschwitz.) More than 400,000 Hungarian Jews already had been deported to their deaths, but some 200,000 residing in Budapest were still safe – temporarily.

In August, however, the Germans overthrew the Horthy government and replaced it with a regime headed by the fascist, anti-Semitic Arrow Cross movement. Anti-Jewish violence erupted throughout Budapest and rumors were rife that the deportations would soon resume. Wallenberg designed a “protective passport,” which gave the holder a Swedish semi-citizenship that in most cases enabled Wallenberg to shield them from deportation; he distributed thousands of them to Jews in Budapest. There even were instances in which Wallenberg climbed to the roof of a train car that was about to take Jews to Auschwitz and handed out the passports to the captives inside, resulting in them being taken off the train.

An estimated 10,000 Hungarian Jews found shelter in the 31 buildings that Wallenberg rented in Budapest. Funds for these operations came almost entirely from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the World Jewish Congress; the Roosevelt administration gave the War Refugee Board only token funding, even though it was a U.S. government agony.

Carlberg reiterates the well-known story of Wallenberg’s work in Hungary, but adds many fresh details about both his personal life and his rescue activities. It would have been helpful if “Raoul Wallenberg: The Biography” included the author’s source notes – even in abbreviated form – in the book itself, rather than on a separate website. The final result is an exciting and engaging chronicle, but the format makes it difficult for the reader to know what sources were used for much of what Carlberg writes.

Missed opportunities

At first, the Kremlin promoted the idea that Wallenberg was murdered by the Arrow Cross and never arrested by Soviet forces at all. Later, Soviet officials claimed he died of a heart attack (even though he was just 35 and in good health) while in a Soviet prison. The evasive and contradictory statements by the Soviets made it obvious they were hiding something. Yet successive postwar Swedish governments declined to press for answers regarding Wallenberg, for fear of annoying the Kremlin. Opportunities to free him, or at least to find out what happened to him, repeatedly were missed.

Despite Ingrid Carlberg’s impressive efforts, the full story of what happened to Raoul Wallenberg in Soviet custody may never be known, although clues continue to surface. Just this summer, the newly discovered diary of a senior Kremlin official was found to matter-of-factly refer to Wallenberg being “liquidated” on the orders of Premier Josef Stalin and Foreign Minister Vyachelsav Molotov.

The most important question for future generations is the one that cannot be answered: Why would a Swedish businessman with no particular connection to Jewish matters risk his life to save Jews in a country a thousand miles away? Perhaps all one can say, in the end, is that in every generation, there are a handful of people who somehow rise to the occasion. We can only be grateful that in this case, the hero’s personal courage was matched by a persistence and resourcefulness that resulted in saving many tens of thousands of innocent lives.