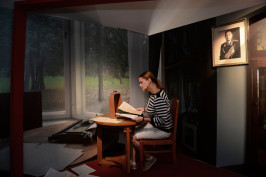

Vera Serova, the only grandchild of General Ivan A. Serov, worked with the Russian Military-Historical Society to create an exhibit about him linked to the publication of his diaries. They were found in suitcases hidden in a wall. Credit James Hill for The New York Times

Vera Serova, the only grandchild of General Ivan A. Serov, worked with the Russian Military-Historical Society to create an exhibit about him linked to the publication of his diaries. They were found in suitcases hidden in a wall. Credit James Hill for The New York TimesMOSCOW — The 1945 disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg — a Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Hungarian Jews from Nazi gas chambers — ranks among the most enduring mysteries of World War II.

Suspicion for the snatching of Wallenberg off the streets near Budapest fell almost immediately on the Soviet Union. To the Soviets occupying Budapest, the ties that Wallenberg had forged with senior Nazis and Americans smelled like espionage, with rescuing Jews an implausible cover story. But his disappearance went unexplained, right through the Gorbachev era of glasnost and the chaos after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

This summer, however, the newly published diaries of the original head of the K.G.B. — found secreted inside the wall of a dacha — have shed fresh light on the case by stating outright for the first time that Wallenberg was executed in a Moscow prison.

“I have no doubts that Wallenberg was liquidated in 1947,” wrote Ivan A. Serov, a Soviet military man who ran the K.G.B. from 1954 to 1958.

Tantalizing hints that Wallenberg, the scion of a rich, prominent family of Swedish industrialists, was imprisoned in Moscow emerged immediately, then dripped out at long intervals. Alexandra M. Kollontai, the domineering Soviet ambassador to Sweden, initially told Wallenberg’s mother that the diplomat was in custody, but backtracked after the Kremlin announced that it knew nothing of the case.

In the 1950s, Moscow began releasing war prisoners, and some reported meeting a V.I.P. inmate. Some called him mysterious; some knew his name. Sweden started asking pointed questions, and seeking to improve ties, the Kremlin released a report in 1957. It said a newly discovered, partial medical report indicated that Wallenberg, age 34, died of a heart attack in prison in July 1947 — a stock Soviet cover story.

On display in the Serov exhibit were family items such as chess sets and a lacquer box with a family portrait. Credit James Hill for The New York Times

On display in the Serov exhibit were family items such as chess sets and a lacquer box with a family portrait. Credit James Hill for The New York TimesThe next halting step toward resolution came with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. The Kremlin agreed to cooperate with a comprehensive Russian-Swedish effort that included archival research and interviews with retired state security employees.

But the final report in 2000 reached no definitive conclusion about Wallenberg’s fate, and found that documents had been destroyed or altered to eliminate all traces of him.

In time, Wallenberg’s rescue work became an lasting symbol of the international human rights movement, but the mystery of his fate seemed likely to endure forever — until the Serov diaries came to light.

Memoirs from high-ranking Kremlin officials are exceedingly rare, and this one, while hardly definitive, contains several references to previously unknown documents on Wallenberg.

They include a report about Wallenberg’s cremation, and another quoting Viktor Abakumov, who preceded Serov as head of state security but was tried and executed in 1954 in the last Stalin purges. Abakumov apparently revealed during his interrogation that the order to “liquidate” Wallenberg had come from Stalin and Vyacheslav M. Molotov, the foreign minister.

The word “killed” has never appeared in any official documents released from the Soviet side, according to Nikita Petrov, a historian with the Memorial organization in Moscow who specializes in the Stalinist era and Serov himself.

Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat and World War II hero who disappeared in 1945. Credit Pressens Bild/Associated Press

Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat and World War II hero who disappeared in 1945. Credit Pressens Bild/Associated Press“They did not use this word,” Mr. Petrov said. “They said it appears he was killed, but we know nothing about this, we don’t have any documents. In Serov’s diary, you can find this word as a fact.”

Memoirs lack the weight of official documents, Mr. Petrov noted, but Serov also described reading a Wallenberg file. Previously, the security service denied that any such files existed, according to diplomats, historians and others who have long worked on the case.

“There should have been a personal or prisoner file which was created for every prisoner,” said Hans Magnusson, a retired senior diplomat who directed the Swedish side of the Swedish-Russian Working Group. “The Russians said that they did not find one.”

The Serov book is called “Notes From a Suitcase: Secret Diaries of the First K.G.B. Chairman, Found Over 25 Years After His Death,” and appeared in Russia in June with its own extraordinary tale.

Four years ago, Serov’s only grandchild, Vera Serova, 57, a retired ballet dancer, hired workers to renovate the garage at the dacha she inherited from her grandfather in northwestern Moscow. The workers demolishing the internal walls stumbled upon a few hidden suitcases.

“They thought it was money or gold, but it was only papers,” she said in an interview, flashing a smile. Mr. Petrov said the suitcases probably went into the wall around 1971, when the Central Committee first got wind of the writing project and had Serov followed.

Mrs. Serova turned over a copy of the diaries to a publisher, who condensed them into a single, 632-page volume. The book was released in conjunction with a small museum exhibition curated by the Russian Military-Historical Society.

The exhibition skips the dark periods in Serov’s career. There is no mention of his role in organizing the mass deportations of minorities deemed potential wartime collaborators, nor establishing the secret police used to eliminate opposition to Soviet rule in East Germany and Poland.

After leaving the K.G.B. for military intelligence, Serov was eventually disgraced after one of his underlings was exposed as a Western spy. He died of a heart attack in 1990 at 84.

Mrs. Serova said she had published the diaries to restore her grandfather’s reputation. “It is important for me because we wanted to rehabilitate his name. Very few people in Russia know him, almost nobody,” she said. “He was acting on the orders of Stalin and others.”

In the half-dozen pages devoted to the Wallenberg case — somewhat sketchy and written in dry, bureaucratic language — Serov said Nikita S. Khrushchev, who succeeded Stalin as Soviet leader, had asked him to investigate what happened, respond to Sweden and help purge Molotov. Serov wrote that ultimately he failed to uncover the full circumstances of Wallenberg’s death, and found no evidence that he had been a spy.

Foreign governments and researchers have long suspected that Moscow was withholding documents, unwilling to confirm that Stalin would coldbloodedly order the murder of a foreign diplomat rather than admit that the Kremlin had been lying.

Serov’s identity cards, also on display. The memoir material sheds new light on the long-unsolved Wallenberg case. Credit James Hill for The New York Times

Serov’s identity cards, also on display. The memoir material sheds new light on the long-unsolved Wallenberg case. Credit James Hill for The New York TimesThe most important document never released is a letter from Abakumov to Molotov on July 17, 1947, which researchers believe contains the details of Wallenberg’s death. In the archival material that was released, researchers found a note scrawled in the bottom corner of another letter saying that “Ab,” or Abakumov, wrote a personal letter to Molotov and giving the document’s reference number.

Letter 3044/a was listed in a K.G.B. register of outgoing letters, according to the Russian-Swedish report, showing that it was despatched on July 17 and indicating that it concerned Wallenberg. A different memo said it had been received. But the actual letter has never been found.

“The Russian side’s explanation for this is that the letter was personal and particularly sensitive in character,” said the joint 2000 report.

Marie Dupuy, Wallenberg’s niece and heir to the sustained clan effort to unearth the truth, said she would like to see the original diaries and ask the F.S.B., the successor agency to the K.G.B., for the documents mentioned by Serov. “Numerous questions remain about the source material, which must be thoroughly evaluated before any conclusions can be drawn,” Ms. Dupuy said in a statement on her website.

Last year, historians with long experience on the case organized the Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative, a renewed, international attempt to comb the archives, and they have compiled a 33-page list of questions for the Russian government.

The media office of the F.S.B. did not immediately respond to questions about whether it would release the documents Serov mentioned or cooperate with renewed research.

Perhaps the underlying Russian attitude was succinctly summed up by Khrushchev, whom Serov quoted as uttering a blunt Russian expression after being briefed on the case.

“These scoundrels,” he barked, naming Stalin and his coterie, “brewed this rotten porridge, while we have to gulp down the sewage.”