During World War Two, a young Swedish diplomat saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Nazis. But in January 1945 Soviet troops arrested him – he was never seen in public again.

The day German soldiers arrived in Budapest is one that 89-year-old Marianne Balshone will never forget.

She was due to meet her fiance, Pista, on the quay of the Danube but he called to tell her that German troops were crossing the bridges of the city – he told her to stay at home.

“From that day on, everything went downhill… that was the beginning of the end of my youth,” says Balshone. She was 17 years old at the time.

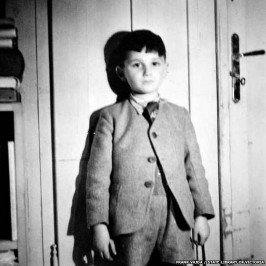

Frank Vajda also remembers that day. As an eight-year-old, he watched as the German tanks rolled into his city. “They came roaring by and I remember the people being ecstatic… all giving the Hitler salute and screaming… I was horrified.”

Both Balshone and Vajda were part of Budapest’s Jewish community. They, like other Jews in Hungary, had been subjected to discrimination and anti-Semitic laws. But because of Hungary’s alliance with Germany, Hungarian Jews had, until that point, been insulated from the horror experienced by Jews in other parts of Europe.

That was to change drastically – Hitler had begun to distrust the Hungarian leader Miklos Horthy and on 19 March 1944, German forces occupied Hungary.

In the weeks and months that followed, hundreds of thousands of Jews across Hungary were rounded up, moved into ghettos and forced on to deportation trains.

With the help of the Hungarian government, the Nazis deported 440,000 Jews from Hungary in the space of two months – most were sent to the largest and most infamous death camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

So in the summer of 1944, Sweden – with US backing – agreed to use its diplomatic mission in Budapest to help Hungary’s remaining Jews.

Thirty-one-year-old businessman Raoul Wallenberg came from one of Sweden’s wealthiest and most important families – he had no diplomatic experience and had studied architecture at university, but his charisma marked him out.

He was appointed Sweden’s special envoy and arrived in Hungary in July – by that time the only Jewish community left in the country was in the capital Budapest according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“They organised the deportations first from the countryside. The decision was made to empty Budapest last, so there were still Jews left there for Wallenberg, the other Swedes and the other neutral diplomats to do something,” says Dr Paul Levine, author of Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest: Myth, History & Holocaust.

Balshone recalls hearing about Wallenberg’s arrival, and remembers being told that he was “coming to Budapest to save the Hungarian Jews”.

Her father had just been arrested by the Gestapo and was in a holding camp in Budapest – Balshone knew it was a place from where many people started their journey to Auschwitz. But a piece of paper distributed by Wallenberg saved his life.

Before Wallenberg’s arrival, the Swedish embassy in Budapest was already issuing travel documents to Hungarian Jews – these special certificates functioned as a Swedish passport.

The papers had no real authority in law but the Swedes managed to persuade the Hungarian authorities that people holding them were under their protection.

When Wallenberg arrived, he decided that the certificates needed to look more official so he redesigned them. He introduced the colours of the Swedish flag, blue and yellow, marked the documents with government stamps and added Swedish crowns. It was known as a Schutz-Pass or protective pass.

Wallenberg negotiated with the Hungarians to allow him to issue nearly 5,000 Schutz-Passes but according to the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, he issued more than three times that number.

Some people queued at the Swedish embassy in Budapest for them, but Wallenberg and his staff also delivered passes to Jews throughout city.

One of Wallenberg’s drivers recounted how the diplomat intercepted a train about to leave Budapest for Auschwitz. “[He] climbed up on the roof of the train, carrying a bundle of passports and started to hand them over to hands eagerly stretched out through open doors.”

Wallenberg ignored the Nazi and Hungarian guards who were firing warning shots and ordered anyone who held a protective pass to get off the train, saving them from “a voyage of horror and death.”

Balshone managed to get a Schutz-Pass delivered to her father. “Lo and behold the Gestapo acknowledged this piece of paper,” she says. “And the next day my father appeared at the threshold of our house, gaunt and beaten but alive.”

Wallenberg also bought and rented more than 30 buildings in Budapest including hospitals and a soup kitchen – he hung Swedish flags from their front doors and declared that they were protected by Swedish diplomatic immunity. At least 15,000 Jews moved in for protection and hundreds more worked for Wallenberg.

Months later, Wallenberg saved another member of Balshone’s family. By this time, she and Pista were married and they had moved into the basement of one of Sweden’s diplomatic offices in Budapest for safety.

Like others living there, Balshone would take her turn at operating the office’s telephone switchboard on the first floor. One morning, as she was about to start her shift, she looked out of the window and saw soldiers marching towards the basement.

“Everyone, including my husband, was hauled out into the snowy streets of Budapest to be taken to the Danube,” she says.

She feared the worst – Hungarian fascist forces, with the support of the Germans, regularly took Jews to the banks of the Danube and shot them letting the bodies fall into the river. “Back then the Blue Danube became the Red Danube,” says Balshone.

She had access to the switchboard so she called Wallenberg’s office to tell him what was happening – she later heard that he went to the Danube and confronted the troops.

“He said to these horrible soldiers, ‘You cannot take these people away, they are all Swedish citizens. Show your papers people!'”

Some of those captured had their Swedish Schutz-Passes with them, others did not, but everyone did what Wallenberg said and held up whatever documents they had.

“Believe it or not, this Raoul Wallenberg had such power and charisma and God knows what gave him the strength – but they let everybody go and my husband returned,” says Balshone.

Eight-year-old Frank Vajda and his mother, Maria, were ejected from their small Budapest flat shortly after the German occupation – the concierge of their apartment building had informed the authorities they were Jewish. They were ordered to go to the ghetto but they decided to move into the hospital where Vajda’s mother worked as a paediatric nurse.

His father had been part of the Hungarian “labour service” where Jewish men were forced to build roads and railways – many were treated terribly and lived in awful conditions. Frank clearly remembers the day he was playing with his toys on the floor of their flat when his mother told him to kiss his father goodbye – he never saw him again.

While living in the hospital, Vajda heard that some people had Swedish passports and he remembers flags of neutral countries hanging on the wall. Then on 16 October 1944 he met Wallenberg in person.

“I was coming in from the back garden of the hospital where I used to play,” he says. “I found my mother embroiled in a violent argument with heavily armed guards.”

The men were from Hungary’s fascist Arrow Cross party and Vajda begged his mum to stop arguing with them.

About 30 people, including Vajda and his mother, were marched out of the hospital and along the street to a military barracks. They entered the parade ground, and everyone was told to line up against a wall in front of a machine gun.

“One of the women with us fainted and I asked my mother, ‘What’s going on?’ She told me, ‘the woman fainted because the men were debating whether to shoot us there or take us to the Danube.”

At that point, several civilians arrived at the military barracks – one of those was Wallenberg. Vajda remembers him standing in a huddle talking with the armed guards about 15 yards away.

The discussion went on for about 10 minutes and in that time, Vajda recalls trying to work out if it would be better to die there in the parade ground or at the Danube.

“And then suddenly they finished their chat, they came over to us and we were taken back. No explanation, nothing. But all of us were taken back where we came from and we couldn’t believe it.”

There are many stories like these – but how did one man have so much influence and save so many people?

“There’s no question he was certainly a special individual – charismatic and highly intelligent,” says Levine. “But it’s very important to remember that Raoul Wallenberg was a representative of a sovereign government recognised by the Hungarians and the Germans. Therefore he had a status and standing enabling him to negotiate.”

As the Soviets closed in on Budapest, Wallenberg’s final achievement was to persuade the Nazis to stop the planned annihilation of the main Jewish ghetto in Budapest, which was home to 70,000 people.

The German general in charge received a letter from Wallenberg – in it he promised the general would be held personally responsible for the ghetto’s destruction and would be hanged as a war criminal once the war was over.

The planned massacre was stopped – Marianne’s grandfather was in that ghetto and was her third relative saved by the Swedish diplomat.

Despite saving so many people, Wallenberg’s own life had a sad and unexplained ending. In January 1945, after the Soviet Union captured eastern Budapest, Wallenberg was detained by Soviet troops. It was the last time he was seen in public.

It’s not clear why they arrested him or how he died. In 1957 the Soviet foreign minister released a report to the Swedish authorities saying that he had died of a heart attack on 17 July 1947 in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison.

But in 2009, two US based researchers investigating Wallenberg’s death received a letter from the FSB, Russia’s secret police. It said that “with great likelihood”, Wallenberg had been renamed “Prisoner No. 7” and that there were records of that prisoner being interrogated on 23 July 1947 – six days after his supposed heart attack.

There are also reports from prisoners, other detained diplomats and even a cleaning lady at one prison who reported seeing a Swede who resembled or called himself Wallenberg. Some of these eyewitnesses say they saw him in prison many years after 1947.

There have been several investigations into his disappearance but none have provided any conclusive answers.

“There is no final proof. The witnesses who claim to have seen him have varying degrees of credibility but none have been proven completely credible,” says Levine. “So the best evidence we have is that he was murdered in July 1947 as an inconvenience.”

Some have suggested that the Soviets were suspicious of his humanitarian work – that they thought he had some other motive. Or they may have suspected he was an American agent.

“It’s easy to speculate that he may have been a spy, but there’s no evidence of that,” says Levine. “All the other Swedish diplomats were also in Soviet detention for some weeks but they made it back to Stockholm. Wallenberg was not released back and we still don’t know why for sure.”

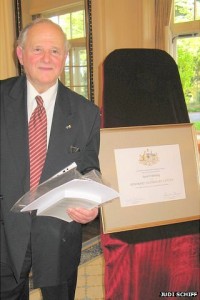

Despite this, Wallenberg’s memory is kept alive by those he saved – 70 years on, people like Balshone tell his story to younger generations studying the Holocaust in schools and universities. And Vajda, now a Professor of Neurology in Melbourne, petitioned the Australian government to recognise Raoul Wallenberg as that country’s first and only honorary citizen.

“If I could meet him now, I would shake his hand, kiss his cheek and hug him,” says Balshone. “I would tell him, ‘You are a saviour, an unbelievable human being and we all thank you from the bottom of our hearts.'”