Millions Of Nazi Documents Are Being Made Available To The Public

For the first time, secrets of the Nazi Holocaust that have been hidden away for more than 60 years are finally being made available to the public. We’re not talking about a missing filing cabinet – we’re talking about thousands of filing cabinets, holding 50 million pages. It’s Hitler’s secret archive.

The Nazis were famous for record keeping but what 60 Minutes found ran from the bizarre to the horrifying. This Holocaust history was discovered by the Allies in dozens of concentration camps, as Germany fell in the spring of 1945.

As correspondent Scott Pelley reports, the documents were taken to a town in the middle of Germany, called Bad Arolsen, where they were sorted, filed and locked way, never to be seen by the public until now.

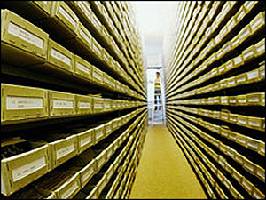

The storerooms are immense: 16 miles of shelves holding the stories of 17 million victims – not only Jews, but slave laborers, political prisoners and homosexuals. To open the files is to see the Holocaust staring back like it was yesterday: strange pink Gestapo arrest warrants as lethal as a death sentence, jewelry lost as freedom ended at the gates of an extermination camp. Time stopped here in 1945.

Millions of records kept by Nazi Germany are going to be opened to the public.

Millions of records kept by Nazi Germany are going to be opened to the public.Pelley walked through the evidence with chief archivist Udo Jost. He showed 60 Minutes a list of 1,000 prisoners saved by a factory owner who told the Nazis he needed the prisoners labor. This was the list of Oskar Schindler, made famous by the Steven Spielberg movie.

”Here are the 700 men and the 300 women whose names were on Schindler’s list,” Jost explains.

The 60 Minutes team also found the file of ”Frank, Annaliese Marie,” better known as Anne Frank. It’s her paper trail from Amsterdam to Bergen-Belsen, where she died at the age of 15.

But most of the names here are of unknown people. While the Nazis did not write down the names of those executed in the gas chambers at places like Auschwitz, they did keep detailed records of millions of others who died in the camps. Their names are listed in notebooks labeled ”Totenbuch,” which means ”death book.” The names are written here, single-spaced, in meticulous handwriting.

”Here we see the cause of death: executed. And you can see, every two minutes they shot one prisoner,” Jost explains.

”So they shot a prisoner every two minutes for a little over an hour and a half?” Pelley asks.

”Yes. Now look at the date: it’s the 20th of April. That was Adolf Hitler’s birthday. And this was a birthday present, a gift for the Führer. That’s the bureaucracy of the devil,” Jost says.

The devil is in the details – the smallest details. Pelley and the 60 Minutes crew were amazed to see the Nazis kept records of head lice.

”You can see the names and numbers of each prisoner, and the amount of lice that were found,” Jost says.

The Nazis couldn’t have disease spreading among slave laborers. ”You can see he was a perfectionist. He even put down the size of the lice. Large, small or medium-sized lice,” Jost comments about the Nazi lice inspector.

Paul Shapiro helped pry open the archive. He’s Director of Holocaust Studies of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C.

”I’m curious. Why did the Nazis keep all these records? If they were gonna murder these people anyway, why keep the paperwork?” Pelley asks.

Walter Feiden, Michael Schwartz and Jack Rosenthal.

Walter Feiden, Michael Schwartz and Jack Rosenthal.”Because they wanted to show they were getting the job done. So, in terms of people whose destiny was to be murdered, recording how well that was being done was very important,” Shapiro explains.

And those records make up the largest Holocaust archive anywhere. Run by the Red Cross, the International Tracing Service was set up after the war to trace lost family members. Survivors could write for information, but there was a backlog of 400,000 unanswered letters. And neither survivors nor scholars got past the lobby.

”What was the stated reason for keeping these documents out of the public eye for more than 60 years?” Pelley asks.

”A respect for privacy of individuals was the most-often cited reason,” Shapiro says. ”On the one hand, you had governments stating ‘We’re protecting people’s privacy.’ And on the other hand, you had those very people saying ‘No, no, we want the material to be open.’”

When Germany, last spring, became the last of 11 countries to agree, they began the process of opening the archive. It will take about a year. But 60 Minutes brought three men to Bad Arolsen for an advance look.

Walter Feiden, Miki Schwartz and Jack Rosenthal are the first Holocaust survivors ever in the archive.

Schwartz, of San Diego, was 14 when he watched his parents herded to the gas chambers at Auschwitz and then, later, was forced to sign himself in at Buchenwald.

Schwartz came across some documents bearing his handwriting.

60 Minutes asked the Red Cross to find all the documents for these three survivors. There were plenty of surprises, including a mysterious reprieve.

”This is a transport list for prisoners leaving Buchenwald and going to a camp called ‘Dora,’” Pelley remarks. ”You know what Dora was?”

”Yes,” says Schwartz. ”Some sort of a fabrication of armaments.”

The arms fabricated at Dora were the V-1 and V-2 rockets that rained on London.

”And the story of that place is, hardly anybody got out of there alive. Look at your name. It’s on the transport list to go there. And somebody’s drawn a line straight through the middle of it. They took you off the list. Did you know until this moment that you were headed to Dora?” Pelley asks.

”No. Never, never, never, wow,” Schwartz says. He had no idea why he was taken off the list. Of 50 people named, he was one of just two with a lifeline straight through his name.

”I’m sort of, yes I’m shaking. I’m scared right now,” Schwartz says.

”Right now, it makes me think back, and I’m living like there is this 14-year-old youngster and they wanted to kill him,” Schwartz says. ”I don’t know why, I did not ever do anything, any harm to anybody. I think I should have a middle name, my middle name to be Mr. Lucky.”

Secret archives kept by the Nazis have been tightly controlled since the end of World War II, but are about to be made public.

Secret archives kept by the Nazis have been tightly controlled since the end of World War II, but are about to be made public.Walter Feiden, of New York, was 13 and a prisoner in a Nazi ghetto, where both his parents died. Later, he too signed into Buchenwald.

Among the documents was the paper Feiden signed. ”Hey, you’re right. I had better handwriting then than I have now, but, yes,” he remarks.

”Who was the boy who signed this card?” Pelley asks.

”A young, actually, teenager who had gone through a great deal, become less trusting of what’s told to him. … But glad to be alive. You got to overcome it,” Feiden says.

Asked what he has to overcome, Feiden tells Pelley, ”The breaking down. Because that’s one thing we never did in camp. We never wanted to break down in front of some of SS men, and give them the pleasure of seeing us breaking down.”

”How do you stop yourself from breaking down?” Pelley asks.

”I chew my lips. Have you noticed that the lower lip…” Feiden explains. It’s what he did in the camps. ”Oh, yes and you have to swallow after that. That helps also,” he adds.

A card carried his barracks number, ”66.” That number alone opened his memory. In Block 66, Feiden says a thousand people lived.

”Oh yeah, that’s correct. That’s correct. Oh, oh, my God, what just popped into my mind. Between each block there was a trough you could urinate in. And I can see it now: the block manager, whatever, felt that this person is just about dead. We put these near-dead people into that trough that other people urinated into, and let them die in those things. The brutality of it, you know?” Feiden recalls.

Jack Rosenthal, of New York, arrived with his family at Auschwitz. During the selection process after their arrival, Jack and his uncle were sent to a barracks while his mother and five sisters and brothers went straight to the gas chambers and the ovens.

”I remember that night,” Rosenthal says. ”There was a little window in the barracks where we were. He told me: ‘Look out the window. What do you see?’ and I said ‘The sky is aflame.’ The sky is burning, you know. You saw the flames licking the sky. The stench was terrible. You smelled burning flesh.”

His family burned that night. Yet, incredibly, 60 Minutes found the Nazis had bothered to create a form to keep track of Jack’s mail at Buchenwald.

”But as you can see, there are no records of letters. You didn’t…” Pelley remarks.

”Who was gonna send me mail? I got news for you, if I would have died in Buchenwald, nobody would ever shed a tear for me, because my, my whole family was wiped out before then. We were a family of eight. And I’m the sole survivor.”

American soldiers liberated Jack in 1945. On a personal effects card that he had signed at Buchenwald, there was reference to a number: A11832.

Asked if he’s seen that number before, Jack tells Pelley ”I see it every time. You wanna see it?”

A11832 is the inmate number the Nazis tattooed on Jack’s arm. ”It’s there. And when I die, they shouldn’t cover up my arm. They should keep it like this, because when the good Lord will see this, I hope he’s gonna put me front row, center. Because I deserve it,” he says.

These men were first to see their documents, but the Bad Arolsen archive is being digitally scanned, to be distributed to research centers. Other survivors may yet discover unknown history still waiting to be written.

Asked if he’s glad he looked back at the documents, Miki Schwartz tells Pelley, ”Definitely. I feel like I learned about me, at least, what happened and specifically what I’m glad about, for those people who said the Holocaust didn’t happen, like the president of Iran. If they have any questions about it, please come to Bad Arolsen and check it out for themselves.”