I was born on 30 January 1927 in Beckum, a small town near Münster in Westphalia. That happened to be to the day, six years before the Tag der Nationalen Erhebung, which roughly means the Day of National Spiritual Uplift, – i.e. the day Adolf Hitler assumed power in Germany (30 January 1933) and became Reichskanzler. That day was to influence my entire future life. But it also had the pleasant consequence that during my first six school years I enjoyed a day off on my birthday, as the day had been decreed a public holiday…

My father Jacob Raphael (b. 1897 in Posen, d. 1971 in Ramat Gan), was the teacher at the local Jewish elementary school. He was also the Hazan, and in fact was the spiritual leader of the community. That was the custom in those days in the smaller Jewish communities in Germany: The teacher, apart from functioning as such, usually performed all the functions normally carried out by a rabbi – including weddings and burials – but not those of the Mohel and the Shochet. Incidentally, my father’s predecessor in Beckum had been Lehrer J. Osterman, the grandfather of Uri Avnery…

My mother was Lilly Fischer (b. 1901 in Vienna, d. 1991 in Haifa).

After 1933 the small local Jewish community shrunk steadily. The feeling at the time was that in the smaller towns where everyone knew each other, it was more difficult to live with the anti-Jewish legislation being introduced by the Nazis. In the larger towns one had a better chance to untertauchen, i.e., to maintain anonymity. Anyhow, that was the theory.

In May 1937 my father thus took up an appointment as teacher at the Israelitische Gartenbauschule in Ahlem near Hanover. I became a pupil at the boarding school that was attached to that institute. It was the start of a very different way of life for me. From almost complete isolation from children of similar age, I was introduced, at the age of ten, to the very special code of behaviour of a boarding school. It was a new and completely unfamiliar experience.

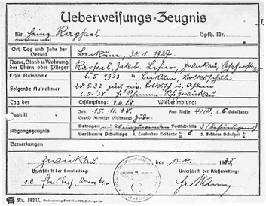

A year later, in May 1938, we moved again, this time to Zwickau in Saxony. My father’s official title in Zwickau was Prediger, i.e., preacher or clergyman. Again he was teacher, but this time for Jewish subjects only, as there was no Jewish general school. For me it was to become another change. In 1938(!), at the age of eleven, I was to go for the first time to a non-Jewish, an Arian school, the Hans-Schemm-Schule I lived completely apart from my fellow-pupils. I don’t recall that they were particularly nasty to me; they simply ignored me.

Not long after this, in November, there followed the fateful Reichspogromnacht. I was in bed, ill with the measles. The Gestapo visited us in the morning. They knew my father from his visits as Seelsorger (”minister”) to the Jews in the local prison. [From Papa’s report: ”There were only ‘foreign’ or stateless Jews in the prison. Almost solely for minor offences, such as passport problems and residence permits etc. There were no ‘political’ prisoners. There were no reports of ill-treatment.”] They behaved with consideration, and didn’t bother the sick boy in the bedroom. The living room was demolished. Bookshelves and sideboard were toppled over. Our large Goethe (!!) portrait was smashed with an axe. The place looked very much in shambles, but after it was cleared up, the damage wasn’t great.

Translation of Papa’s report (to A. Diamant, Frankfurt, 13.6.69): ”… In the Kristallnacht the Burgstraße synagogue was destroyed. Next morning SS-men appeared in the Jewish apartments. They made some noise, but there was no actual ill treatment. Also in our apartment in the community house (Elsasserstraße 65) appeared an SS-man, without, however, causing much ‘damage’ (apart from the glass of a clock). I was asked to get myself ready. After a brief ‘march’ through the streets, past the Burgstraße [synagogue], the Jews (the men; no children) were taken to the police headquarters. Then we were transferred to the prison; the cells were clean and the treatment was fair. (Only teacher Mordehai Fingerhut with his Palestine passport was released and sent home!) After three or four days we underwent a ‘medical check’ (Mr Ledermann was released because of a heart ailment), and we were transported to Buchenwald. There I did my best to take care of our people, and to keep them in good spirits as far as that was possible. In spite of much chicanery, there was no real ill treatment of our people. I was released after about three weeks (they needed me to liquidate the community), and so were all the other ‘colleagues’. No one was left behind.” According to a card in the Arolesen-Micro-Archive my father was released on 8.12.38. I remember that he returned during Hanukah. The Buchenwald experience had one effect on my father: for a brief period he put on Tefilin each morning…

I was expelled from the Hans-Schemm-Schule on November 15th, after I had recovered from the measles. The official reason for the expulsion was duly recorded on the document: ”Jude”. There was an interesting episode. After I had received the document at the school office, I returned to the classroom to collect my things. The teacher Herbert Mann accompanied me out of the classroom, and we walked along the long corridor. He put his hand on my shoulder and asked: ”Is your father at home?” I answered ”No”. He tried to comfort me: ”He is sure to return home soon. I know that.” That was all. Like all teachers at that time, Mr Mann wore the NSDAP party badge on his lapel. The gesture was a small one. But considering the psychosis of those days, and the systematic brainwash, it pointed at courage and independent thought. Many years later, in 1990, after things had changed in the DDR (East Germany), I tried to locate this teacher. I managed to find his son Werner, and received a couple of letters from him, with interesting references to that period in 1938, and also to the situation in East Germany in 1990, i.e., just before the reunification of the two Germanys.

After the Pogromnacht things changed radically. Apart from some odd lessons given by Fingerhut and by my father, we received no schooling at all. At some stage we had ”Israel” and ”Sara” officially added to our names. Jacob was considered sufficiently Jewish in itself, and the addition was not required. But Papa had the ”Israel” added anyway. We also received a Kennkarte (identity card), which included fingerprints and a photograph showing the left ear…

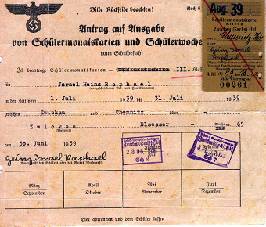

Shortly after the Pogromnacht Family Fröhlich (Otto & Hermine) became our upstairs neighbours. Their daughter Ruth and I became close friends. We went for walks along the local river Mulde, and played games together. We even played card games (for the first time in my life, – and also the last). The little schooling we received, we did together. Later, from July 1939, we went daily by train to Chemnitz (49km – see ticket!), together with two other children, to attend the Jewish school there.

All our energy was now concentrated towards emigration. As an active and recognised Zionist, my father was high on the list for a Zertifikat (certificate) to Palestine. In the end he received a commitment by the British government, for a certificate ”within nine months”. At that time it was understood that the Jewish men were in danger in Germany, not so the women and children. The British therefore established a transit camp in England, the Kitchener Camp near Sandwich in Kent, for the men, while the families were to bide their time in Germany, until the certificate would be received. This Kitchener Camp, used to house Jewish Refugees in transit from Nazi Germany, was jokingly referred to as ”Anglo-Sachsenhausen”. (Sachsenhausen had been one of the early German concentration camps.) My father thus left for England in June 1939. In December 1939 he volunteered to the British army, and served until late 1945.

With that promise by the British, to be admitted to Palestine within nine months, my uncle Leo (Fischer, my mother’s brother) succeeded to get a visa to Sweden, for my mother and myself. That was actually already in June of 1939. I don’t really know why it took us until the end of August to leave Germany. We made the arrangements to take our furniture and other belongings with us. The bureaucracy was complicated. Perhaps that was the reason for the delay. An urgent letter is preserved, dated 23.8.39, written by Uncle Leo: ”… I am asking you to leave as soon as possible… Ask your friends to see to the packing and the despatch of your belongings, but you yourselves should leave at once… Do not hesitate to travel even on the Shabbat!…” Actually, for myself a visa to Sweden had been available already since January 1939. Also, at one stage, a certificate was obtained for me for Palestine, thanks to the efforts of my uncles Zvi (Hugo) and Aba Chiya (Fredy). My mother’s cousin Mordehai Avi-Shaul was also involved somehow. My parents hesitated to send the little boy away on his own. Quite understandably, probably.

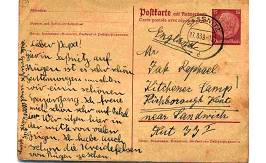

Postcard from Sassnitz

Postcard from SassnitzOn Shabbat 26th August (on my father’s birthday!) we left Zwickau. Via Berlin (Stettiner Bahnhof) we continued to Sassnitz on the Baltic island of Rügen. There we, that is several Jews, were detained for special customs inspection, including a thorough body search. When they finally had finished with us, the ferry for Sweden had left. We spent the rest of the night at the port station. In the morning, in beautiful sunshine, we strolled along the beach, with its famous chalk cliffs. There were rumours that there wouldn’t be another ferry for some time, because of the tense political situation. We wrote a postcard to my father. My mother wrote: ”… We expect to be in Kalmar at about 8am tomorrow morning. But this is uncertain.” Eventually there was a ferry, and we left for Trelleborg. From there we proceeded by train to the railway junction of Alvesta, where we spent the night in a cubicle-like cell, until the early morning train was to take us to Kalmar.

WWII started on 1 September, three days after our arrival in Sweden.

Zeev Raphael

You are invited to visit the RAPHAEL – FISCHER Family Chronicle at

http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/r/a/p/Zeev-H-Raphael/index.html#edit